- A novel concerning art, a clock,

- and unidentified flying objects

To whom it may concern

The persons in this book are fictitious; their identities are not intended to resemble any other persons, living or dead. You might think that the locations are real; however, don’t be deceived by obvious similarities.

Copyright © 2011, 2020 Tom Sharp

Chapters

- Arrival

- Hans

- Clock

- Bonnie

- Thanksgiving

- Inquiries

- UFOs

- Christmas

- Plots

- Incidents

- Detained

- Investigation

- A means

- Return

- Hearts

- An end

Chapter 1. Arrival

Whenever I find myself growing grim about the mouth;

whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul; whenever I find

myself involuntarily pausing before coffin warehouses, and bringing

up the rear of every funeral I meet . . .

— Herman Melville, Moby-Dick or The Whale

- Fall

- The bookstore

- Hired

- Artists and kids

- Cold

- The boarding house

- Reids department store

- Dinners

- History

- Flying

- Ellen

Fall

Fall had turned the plains of central Montana into straw, and had frozen every straw to the earth like miniature fallen forests of piercing quartz needles. I had just arrived in Lewistown from New York. I had been at loose ends. I had wanted (I thought I had needed), to move to a remote spot on the earth. I felt sorry for myself. I thought that “Nowhere Man” by the Beatles described me. And maybe I had read Moby-Dick too many times.

Lewistown is at the geometric center of Montana, and Montana is a large sparsely populated state in the center of the continent. I thought it was sufficiently far from almost everything, including my own tragedies.

Of course this was an oversimplification.

I had been able to take the Greyhound bus only as far as Billings. To travel north from there, I had hitchhiked. I used the traditional method, holding a piece of cardboard that declared my destination, and raising my thumb in the air. I started early in the morning. I was lucky to have flagged a commercial trucker who was going to Lewistown. The trucker came up through Judith Gap, approaching Lewistown from the south west, instead of through Roundup and Grass Range, because he had stops at Harlowton to deliver a hand-truck of boxes to a convenience store, and a stop at Eddies Grove to deliver another stack of boxes to the truck-stop.

From Billings, my ride passed through the small towns of Acton, Comanche, and Broadview on State Highway 3. This was a two-lane road that separated snowy fields on the left from snowy fields on the right. After Lavina, population 200, we turned west onto U.S. Highway 12, and we passed the towns of Ryegage, population 260, and Shawmut, population 45. These small towns were random clusters of struggling trees and homes, where the two-lane highway briefly became Main Street, or Railroad Avenue, or High Street. Lavina had a couple crosswalks without lights or stop signs and one block of businesses. Ryegate had two grain elevators. To the south of the highway was the Musselshell River. To the north, Ryegate was a few small blocks bounded by a crumbling rocky escarpment of about 100 feet in height.

After the truckstop in Harlowton, when we turned off U.S. Highway 12 and headed north on U.S. 191, we were still on State Highway 3. Gravel roads led to small sets of one-story buildings at intervals, with cattle guards marking barbed-wire fencelines. The road led straight across a rolling terrain. Straggling stalks of yellow grass and brown weeds poked up through snowdrifts, particularly at the fencelines. We encountered only a few cars and trucks on the road; these counties seemed basically deserted.

We passed Judith Gap, population 150. It seemed that each tiny block of this small town had only a handful of buildings on it, like an old comb made of bone and missing most of its teeth. The town was surrounded by white fields that in the spring would give people a reason for living there. But to me, having lived in cities most of my life and having worked only in bookstores, these towns had tremendously little appeal. I have to say that I was just passing through, so my impressions of the place were not colored by familiarity or warmed by feelings of the past.

The late Pleistocene Laurentide ice sheet had came south to Lewistown and then stopped. Below and to the east of Lewistown, the large Glacial Lake Musselshell formed, covering a huge area all the way south to Musselshell on U.S. 12 east of Lavina, and draining to the north to join the Missouri River. But as we traversed this frozen landscape, I felt that it could have been a mile under blue ice.

The trucker dropped me off at a McDonald’s on Main Street opposite a three-story brick junior high school.

Fall had started early in Lewistown; it was only the fall equinox. The air was bitterly cold, painful to breathe. The sidewalks were frozen, sheeted with crusty ice. I was not prepared for a wind that cut through my coat as though it were only a T-shirt. Topsider shoes were obviously not protecting toes either. It seemed as though I had just stepped into ice water. I was in it up to the top of my head.

I raised my eyes. Trees dominated the skyline. Looking east past the junior high, on my left, cedar, pine, and larch. On my right, the bare limbs of a birch. I shouldered my bag and gingerly trod along the sidewalk down Main Street. The dome of the county courthouse rose up on my left, with a large four-faced clock at the top, over a four-story two-tone brick building with stone columns, surrounded by large cottonwood and willow, gray and encrusted with snow. Across from the courthouse, a beautiful stone Carnegie library, 1905, with an addition to the basement floor that extended out from under the original structure toward the street. Then a funeral home on the right. I walked another block. A more regular pattern of two and four-story brick and stone buildings began to dominate. The News-Argus. A furniture store. An antique store. A life-insurance office. Office supply. The Magic Diamond Casino, with financial advisers across the street. A Moose lodge. The Western Lounge. A smoke and magazine shop. I began to feel a little more optimistic about my prospects in this old gold town. Pourman’s café. An appliance store. A Mexican restaurant. Bank of the Rockies. The Coffee Cup. A Chinese restaurant next to the small Weaver Block, next to Reids department store. The Lewistown Art Center with vague internal spaces in the imposing Crowley Block building. A hardware store. First Bank of Montana. A liquor store. The Judith Theater.

And there, near the corner of Third Avenue North, an old treadle sewing machine, worse for the weather, was chained and padlocked to a light pole. It looked as though it had been there for more than a season. The machine and its metal legs were rusting; the veneers of its cabinet were peeling. A heavy chain and padlock were obviously part of the installation, not just a means to prevent its removal. The chain wrapped around the cabinet three times, passing through the sewing machine. It had five-eighths welded-steel links, each link spanning over two inches. The padlock looked like it could secure the main gate of a castle.

I was looking for a sign: “Room for Rent,” which I found on a cork board cluttered with business cards and flyers for church socials at the door to a used bookstore. This three-by-five card announced the availability of a room at a boarding house at the corner of West Washington Street and Third Avenue North. I hoped that the boarding house wasn’t too far from downtown.

I stepped back and looked up. The name of the bookstore was Transition. The name seemed appropriate. Used books were in transition. I thought I was a special case, but, in retrospect, it was true of me, too. I was used, and I was looking for new home. I took the three-by-five card from the board and went in to ask for a job. The doorbell jangled. At the counter, Hans looked up.

The bookstore

This was the usual kind of used bookstore, though a rather large one. Real estate was apparently cheap here. The place contained all kinds of books—dime westerns and romances, hardbound coffee-table books, cook books, children’s books, comic books, graphic novels, sheet music, music sets for small orchestras, fake books, foreign language books, sets of encyclopedias, and a bin of free books. Plus a second floor for records, CDs, and posters. And in the front a rack of magazines. All used. It was the detritus of civilization, but at least it was civilized.

The bookstore took up the whole of a two-story brick building named Brooks Block that faced Main. It was big enough to contain two or three businesses of moderate size. The frame of the building was constructed of vertical pillars of tan-colored brick, with joining horizontal elements of carved gray stone. Between the tan and gray on the first floor, from one side to the other, were windows framed in black. Below the main windows were green panels. Above the windows was a green awning. Above the awning was another row of smaller clerestory windows. Above, on the second floor, red brick framed twelve tall windows. At the top, a cornice of stone and brick. Later, I learned the history of the building. It had been a farm-equipment emporium and parts warehouse.

Now Orville and Wilbur owned the building. Whether their own hands had turned it into a used bookstore, I don’t know. Their living quarters were built on a second floor over the storerooms and offices in the back. I think that Orville and Wilbur had a history, too, but they didn’t talk about that, so we need to use our own imaginations. Although they had famous first names, they were not brothers. When Orville and Wilbur worked in the store, they always worked together. In spite of their age—they were old as the hills but were strong and wiry—they traveled a lot, shipping crates of books back to Lewistown from towns and cities about the country and Canada, so they hired a full-time person to take care of the place. This person was responsible for supervising and hiring part-time helpers.

Her name was Sally. She was a gaunt short woman of indeterminate age (but certainly over 50). Sally was always bundled up for winter, with woolen sweater, scarf, and knit woolen leggings under a thick woolen dress of a single color, a dark forest green, or a dull chocolate, or red the color of rust. Her hair was gray and just long enough to be pinned back on the sides with bobby pins. Sally was fierce. Orville and Wilbur must have been proud of the way she defended their interests. She allowed no silliness, no tardiness, and no idleness on the job. Our wages were not high, but it didn’t cost much to live in this town. It is debatable whether any used bookstore in this country can be run as a business, especially in such a small town without a college, but Sally’s point of view was obvious. In my opinion, Orville and Wilbur were saints with an inexhaustible supply of money or credit. But as far as Sally was concerned, to keep the store going, every penny and every minute had to be accounted for.

Hired

Like I said, when I walked into the bookstore the first time, Hans was at the counter. Hans had graying brown hair in a crew cut. He wore a clean T-shirt and corduroy pants without a belt. His face was clean-shaven, his skin was darker than the climate or his employment would warrant, and the beginning of wrinkles about his mouth suggested that he was about my age, that is, in his forties. He was sorting through a tall pile of hardbacks. I went up to the counter, he looked at me, I looked him in the eye. His eyes were blue. I said, “I’d like to work here. Are there any openings?”

Hans pointed toward Sally, who was just coming around a bookcase with a pile of National Geographics. Hans gestured to take my bag, which he put behind the counter.

I repeated my question to Sally, who said, “If you can sort and shelve these in three minutes, we can give you something part time.” But she didn’t give me the pile of magazines right away. She looked me at from head to foot, the way some men look at women, and not with approval.

Sally said, “If you’ve just gotten off the road, maybe you could be excused for being disheveled. But if you get this job, you should know that our employees are expected to be both couth and kempt.”

I was surprised by Sally’s archaic vocabulary, but I nodded and took the pile from her. She pointed out a lower shelf where I could see other National Geographics, and I went right to work.

Artists and kids

An older couple entered the front doors. I could feel a cold draft. I was standing in the aisle that led to the shelves of National Geographic. They walked toward me. The man looked at me up and down and said, “I see you’re new here. My name is Eugene, Eugene Ely, the man with two first names.” The woman, who had been following Eugene, looked around him and added, “His middle name is Burton.” She winked. “I think his mother messed up his birth certificate.”

I told them my name and said, “Yes, I just got in town. I’m glad to meet you both.” Eugene smiled and shook my hand. The woman reached around Eugene and said her name. “Blanche Scott.” She shook my hand and smiled.

Eugene was tall with wild gray hair, made more wild by the static electricity from a navy blue stocking cap that he pulled off as he approached me. They were both bundled up and booted and their cheeks shined red from being outside in the cold. Blanche was short with short red hair and green eyes. She wore a blue ski outfit that matched her eyes.

Eugene said, “We’re artists in search of distant color.”

Blanche said, “He means we want to look for issues of National Geographics that we can cut up.”

Eugene said, “Pages with rare purples and golds.”

Blanche said, “So don’t tell Sally. She disapproves.”

Eugene said, “It’s not her cup of tea. And she thinks ours is already overflowing.”

“Sure,” I said. “I just added an armful of them. I could show you where they went.” I scooched out of their way, and then followed them to the magazine shelves.

I pointed out issues that I had just shelved. Eugene started looking through them, fanning their pages. He stopped with one, put his thumb into it, and said, “Oh, this might do.” He licked his finger and paged through the article.

Blanche said to me, “There aren’t many artists in Lewistown. You should come visit us. Hans can tell you where we live; we’re on West Boulevard Street.”

Eugene said, “Yes, you should, but I warn you that Blanche has got a thing for distant color.”

I smiled at Eugene and Blanche, then walked to the front of the store. The bookstore had an arrangement of mismatched seats and a couple easy chairs around a throw rug near the front. There were five kids on the chairs, and, on the rug in front of them, Hans was reading to them.

The kids weren’t trying to be quiet. One boy was poking another, a stubby forefinger into his side. A girl noticed and opened her mouth, but she only said, to Hans, “Would you read that again, please?” Hans was reading an issue of National Geographic.

Cold

Let me tell you about cold. David Byrne sang about air. “Some people never had experience with air.” But cold is not funny. Cold is like being born in the last century where a sadistic doctor holds you upside down by your ankles and whacks you on your little butt. Cold takes away your power to breathe while it whacks you, so that you cannot even cry. You have no say in the matter.

Cold surpasses cruelty for trying the fortitude of folk. People say that they get used to it. Don’t let them fool you. Actually, what happens is that the cold whips surgeon’s scalpels through the air. You cannot see them, but you can feel them. Over a series of out-patient visits in which Doctor Cold lays its victims on stainless steel operating tables, the doctor performs brain surgery, each time removing a little more of that gray matter that makes them realize that they suffer, so that they lose the ability to realize how cold they are, and of course they forget their time under the knife.

Those with resistance to the scalpel must suffer the cold, and the best that can be said about it is that many of them become proud of their suffering.

You have heard about cold. You have been told. You think that you can be prepared. But when you step outside and experience it, then you experience the misery of cold with your utterly exposed flesh. The skin on your cheeks tries to shrivel on your cheek bones. No part of your body is exempt from cold’s dominion. Immediately you cannot feel your fingers or toes. Needles of cold pierce your flimsy clothing. In bright light you can shut your eyes; when jet engines start you can hold your hands over your ears; but in cold there is no protection; you are naked and everything that you pull over your skin to protect yourself is colder than you are and only drains away your meager and fleeting warmth the faster.

You think that you can prepare for this. You bundle up and bundle down and bundle out with layers of silk and wool and cotton and advanced scientific fabrics, with thermal long johns, double socks, triple and quadruple layers of under and outer garments, with elastic closed legs and sleeves, with insulated boots, with gloves and scarves and hat, with ear muffs and ski mask, but then you step outside, and as soon as you breathe, the cold is inside you. You experience the encompassing and penetrating embrace of the giant of cold who takes away your breath and shocks the blood from every limb and appendage.

In the shock of cold, you may experience a rush as your autonomic nervous system speeds up your heart to pump warmer blood to your extremities, but all your veins are squeezed to the size of capillaries by the invisible vice of cold, and the autonomic nervous system is beaten like a puppy on a rope.

If you neglect to wear your arctic goggles, then the scalpels of cold pierce your eyeballs. Your eyeballs start to freeze. Your vision blurs and you must close your eyes quickly to feel the strangeness of freezing globes under your eyelids. But this is good because your eyelids are not numb. If you can keep your eyes shut, your eyeballs can gradually resume functioning, but this is usually not a practical solution for navigating in the cold, except in ice storms when it is not possible to see anyway.

If you do not protect yourself from cold, it becomes indistinguishable from fire. The treatment for frostbite is to rub snow on the skin. This is a cruel joke of nature (and you were thinking that nature cannot be both humorous and cruel). When you rub snow on frostbite, you activate pain receptors that you didn’t know you had, but this is good because if you experience pain at the ends of your fingers then you will not lose them. If you can feel the cruel needles of cold in your feet then you know that your feet are awakening after near-death.

I had experienced a cold of the soul. I had lost or tossed aside everyone I had loved, or who had loved me. I welcomed the cruel winter that I was entering like a friend. I could understand pain.

The boarding house

Nevertheless, I try not to let my friends hurt me, and I didn’t have a death wish, so after I dropped my bag in my room at Miss Kate’s boarding house, I went out to Reids department store to buy cold-weather gear.

The boarding house was at the corner of West Washington Street and Third Avenue North. It was a large white house with a gray roof on the corner resting beside a large bare elm and a large empty lot. The brick Cloyd Funeral Home & Cremation building was just across the street.

I knocked on the front door. After a minute, Miss Kate answered. She was a short energetic woman in her sixties, I guessed. She wore red lipstick and a heavy corded woolen sweater over blue jeans.

“Ma’am, I just got into town and found this note at the bookstore. I showed her the three-by-five card that I had taken from the cork board at Transitions. Her eyebrows registered recognition.

“If you don’t want to rent a room to me, or if you will have other rooms available, I can replace the card where I found it.”

“Come in. Come in,” she said. She closed the door behind me and said “I’ll take that card, please. Set your bag there.” She pointed to a place by the stairs. She stepped past me as I was putting my bag down and said, “Come into the office where I can ask you some questions.”

The office was a desk and file cabinet at the far end of the living room. I sat down. Miss Kate sat behind the desk and pulled a pen and legal pad from the drawer.

She asked, “How long will you be in Lewistown?”

“At least through the winter,” I said.

“Do you have work here?”

“Yes, I just got a part-time at Transitions, the used bookstore on Main.”

“Good. I’m sure that Sally will be glad to have help,” she said. She took information from my driver’s license and asked me for references. I gave her the name and contact information for Ron, my brother in law, and also contact information for the manager of the previous bookstore where I worked.

She asked if I had a car, adding that there was no carport or garage. I said not to worry about that; I didn’t intend to buy a car.

“For the time being,” I said, “I’ll be walking.”

She said, “That’s not very ‘local.’ A self-respecting Montanan would rather, instead of walking, chip ice off the windshield of his truck, put chains on his tires, jump start his battery, and drive a block.”

I smiled.

She said, “OK, you can take the room for the first week. I’ll talk to Sally and check your references. If I’m not happy then I’m afraid you will need to find another place.”

I nodded.

“In the meantime, you can use the kitchen to make your own breakfasts, and if you do not intend to have a dinner here then I expect for you to tell me before noon. There’s no dinner on Saturdays or Sundays.”

I nodded again and said, “I can do that. OK.”

She looked at me steadily, waited a moment, and said, “You can call me Miss Kate. Oh, and here is a key.” She took a key from the drawer. “It works both front and back doors. Your room won’t be locked, unless you are in it.”

“Thank you, Miss Kate.”

Miss Kate showed me the kitchen, which was a time capsule from the sixties, with heavily painted cabinetry, white with blue trim, copper pulls, yellow Formica countertops, pale yellow KitchenAid appliances, a copper stove hood, and a light blue linoleum floor.

Miss Kate showed me where I could find cereal, fruit, milk, and bread and butter for toast in the mornings. She said that I would wash my own breakfast dishes. She also showed me a shelf where I could store my own foodstuffs. Then I picked up my bag and followed her upstairs.

“How many people do you have living here?” I asked.

“Aside from myself, we have four boarders, including yourself, all men, not that I have anything against women, of course. There is Willy Coppens who works at Reids, the department store, and Raymond Collishaw, who deals cards at the Aces Casino. Raymond is here for dinners only on Mondays and Tuesdays. Lastly, there is Mister Draper. Mister Draper is retired; he had been a mechanic at the airport for years and years.”

Miss Kate showed me a small room at the back of the house. The room featured a twin bed, a small dresser with a mirror, an end table with a lamp, and a caned-seat chair. There was a small closet in the corner. The walls were painted a light orange-vermillion. A thick hand-made quilt lay on the bed. A reproduction of van Gough’s bedroom in Arles hung on the wall beside the mirror. It was the second version, the one with the floor having remnants of light green. The colors of the quilt matched the colors of the painting, light blue and deep yellow with green highlights.

“I hope you’ll find this comfortable,” said Miss Kate. “In addition to the room and the kitchen in the morning, you may use the parlor in the front of the house. You may use the telephone in the parlor for local calls.”

I hoped that the parlor would have a comfortable chair and a good lamp for reading. I asked, “May I use the parlor for reading?”

“Yes, of course.”

“Day or night?”

“Yes, although you would be sharing it with Mister Draper. No one else tends to use it, except to make a local phone call now and then.”

“Who is the person here who works at the department store?”

“Willie works at Reids.”

“Do you think he’s working there now? I really need to get some warmer things to wear.”

Miss Kate agreed that Reids would be a good place to buy boots and gloves.

Reids department store

I don’t shop. My strategy is to wait until I need something, plan where to get it, go there, and buy it.

Reids department store was on Main and Third Avenue North, a block from Transitions. I walked up to Main on Third Avenue. The store was in a two-story stone building. Behind in, in the same building, was the Garden Café and the Emporium, Antiques & Collectables. This part of the building had the same stonework, but was darker, as though only Reeds in the front had been power-washed in recent years. There was no parking on Third Avenue except on Sunday, as signage declared it to be an “Emergency Snow Route.” What, exactly, was an emergency snow route? What kind of emergency would be jeopardized by parked cars? Where did the route lead to? I had no idea.

The building was made of a tan-colored sandstone. The display windows and doors were aluminum framed. Over these was a decorative brown and tan striped awning. Over the awning, the store sign. Above the windows on the second floor, a rectangle of stone was carved with the initials P.M.CO. and the date 1901. Reids had two entrances on Main Street, but the first one was locked. It had a sign pointing to the other set of doors.

The store seemed to feature something for everyone, male and female, young and old, small and large, and it was well heated. I went up to a counter where a small balding man in a dress shirt and slacks was folding shirts and I said, “Miss Kate sent me over here. Are you Willie?”

Willie said, “Yes. How can I help you?”

I said, “I’m new here. I’ve taken a room at Miss Kate’s. I don’t have the right gear for this kind of weather. Can you help me quickly chose some warm and practical boots, gloves, warm shirts, and whatever else you think I’ll need to survive this weather?”

“It will have to be quick because we close at 6.”

It was just after 5 p.m.

Willie asked, “Would this be things to wear in town? You’re not preparing for a winter wilderness experience?”

“No, only for town. I don’t have a car, so I’ll need boots and warm clothes just to get around town. Is the weather much worse than this in the wilderness?”

Willie tried to smile, just to be nice, I thought. Maybe he didn’t have a sense of humor. But he led me over to the Mens department and we chose boots and made a pile of flannel shirts, long underwear, wool socks, gloves, ski mask, wool sweater, scarf, and a long down coat. Willie loaned me the scissors from behind the counter so that, as he totaled the damages, I could cut the prices off the boots and coat. I put these on before carrying the rest back to the boarding house.

Getting these warm clothes on and off was cumbersome, but without them I would not have lasted the winter in Lewistown.

It was the end of my first day in Lewistown, and I had already gotten a job, a place to live, and necessary additions to my wardrobe. Furthermore, I hadn’t taken time to worry about what I had gotten myself into. At the boarding house, I went downstairs for dinner with Willie and Mister Draper.

Dinners

Dinners at the boarding house provided some relief for me. Miss Kate took her dinners in the kitchen with the cook, I hardly ever saw Raymond, and Willie wasn’t communicative, but Mister Draper was friendly and talkative. Mister Draper and I got along splendidly.

I have observed that whether a person talks at the dinner table usually depends on how the person was raised.

In some families, competition for food is such that children who talk instead of chew do not get a second helping and might even miss dessert as they are forced to clean their plates. Natural selection favors the silent ones. In some families children are discouraged from talking with their mouths full, or are told to be quiet to let the adults talk. In some, a parent might insist on silence as a relief from a difficult work environment.

But in other families children learn lively and intellectual discussion techniques. Dinner-table discussions in these families are energetic and rigorous, even competitive.

In my family, an almost religious silence had reigned. Truth had already been established. So I was pleased and surprised by Mister Draper’s genial behavior at dinner.

Willie’s parents must have been the discouraging or domineering type, because Willie did not look kindly on dinner-time discussions. Willie’s scowls, however, did not deter Mister Draper, who seemed glad indeed of having someone new at the table.

Mister Draper was a gentleman of minimum height and maximum belly. He had the shape of a turtle on edge, although to correct the accuracy of this image you have to turn the turtle’s body around inside its shell. Standing or walking, Mister Draper had to lean backwards to keep his balance. When he talked to you his head was so far back that he had to raise his voice to be heard. His face was ruddy cheeked; his hair was thin and white; his forehead slanted back; his eyes were dark and framed by laugh lines; his chin was weak; his mouth was wide; his teeth were yellow but he had a beautiful smile. He always wore a white shirt with a black tie, whose end he tucked into the shirt between the third and fourth buttons, so that it was not seen over his protruding belly button. Over this he wore a Harris tweed jacket loose around the shoulders and hanging in the front from the midsection. He hoisted matching woolen slacks up from below with black suspenders.

The first evening when I came downstairs for dinner, Mister Draper was already at the table reading the business section of the Wall Street Journal, which he must have had mailed to him. Typical image of a man at a table behind his paper.

The dining room was dark. I paused at the doorway and let my eyes adjust for a minute. Dominating the space was a wooden table that could have seated eight or ten, but was set for four at one end. Mister Draper sat at the head of the table. On the side of the room, a dark buffet had piles of clean plates and glasses on doilies. A dim sconce shown weakly over the buffet. Extra chairs sat on the wall opposite from the buffet, which also featured two windows, heavily draped in purple cloth. Reproductions of Dutch paintings hung on the walls. A windmill under ominous gray clouds; a still life featuring pewter and a big silver fish; boats on a canal; portraits of men with beards and hats. The floor was wooden planks and barren. A small chandelier hung over the table with six fifteen-watt decorative bulbs providing just barely enough light to see what you were eating. A door at the back communicated with the kitchen.

Mister Draper heard me come in. Typical image of a man lowering the paper to see over it with raised eyebrows as I took a seat. He saw me, dropped the paper to his side, and smiled.

Dinner was mashed potatoes, pot roast, and green beans out of a can. It wasn’t gourmet, but it was hearty. Mister Draper reached with his fork for a portion of pot roast.

“May I ask who you are?” Mister Draper asked.

“I’m nobody,” I said.

Mister Draper pushed his chair back and stood. He gave me a little bow. He said, “I am not the Cyclops. May I introduce myself? I am Mister Draper.”

Miss Kate had referred to him as “Mister Draper,” and he introduced himself as “Mister Draper.” I never learned his first name, even though I told him mine.

I noticed that Mister Draper wore a masonic pin on his lapel, the ‘G’ inside a carpenter’s square and set of compasses. I said, “Mister Draper, you are a Freemason.”

Mister Draper looked at his lapel, turning it up with his thumb, and smiled. “Yes,” he said. “Brother in good standing of the Friendship Lodge of Ancient and Free Masons of Lewistown Montana.”

“You don’t look ancient,” I said.

“Looks may conceal more than you may see,” he said. “Freemasons built the Temple of Solomon. We built our own temple in 1908.”

I said, “That beats me. I just got off the bus.”

Mister Draper said, “I did not intend to beat you. Welcome to our little town.”

“Thank you. I may appreciate your long acquaintance with this town—you know, to learn whom I must meet and where I must be seen.”

“I would be honored, in any small way that I may, to direct you between the jaws of Scylla and Charybdis.”

“I hope that Miss Kate is neither Scylla nor Charybdis,” I said.

“Oh, no. Miss Kate is as sweet as pie. She really is.” Then Mister Draper whispered behind his hand, winking, “I never bite the hand that feeds me.”

History

One evening, I asked Mister Draper how Lewistown had changed over the years.

Mister Draper said, “We may observe four periods in the history of Lewistown. The first permanent settlement in this place was a trading post, Fort Sherman, built in 1873 on the speculation that the federal government would establish a Crow reservation here. That fell through. But this began what we may call the Cowboy period, which placed a period on the native period, before there was a town here. You may have realized nothing is permanent.”

“All things must pass,” I said.

“The Metis, descendants of natives who intermarried with the French, were part of the cowboy period and were early settlers here before it became Lewistown. This was also when the Carroll Trail was established and, for protecting the Carroll Crossing at Big Spring Creek during the summer months, the U. S. Infantry built a post here that they named Fort Lewis after Major William H. Lewis. You see, the town was not named after Meriwether Lewis. The closest that the Lewis and Clark expedition came was Great Falls, and that’s a hundred miles from here. This period was coarse and violent. The cowboys were of course employed by the ranchers. A romantic view of that period predominates.”

“Charlie Russell documented that period,” I said.

“True, and this is why our boosters call this area ‘Russell Country.’ OK. The second period is the gold rush, which began in 1880. Before this time, the population of the town was under 75, but by 1890 the population was ten times that. A lot of money was lost, but some people become wealthy. The town was plated in 1882, and Croatian stone masons built our old stone and brick buildings then with stone from Big Spring Quarry for the businessmen who had gathered the gold. Lawlessness resulted in an appeal by the town to the state to establish Fergus county in 1886, and to incorporate Lewistown in 1899.”

“Eventually,” Mister Draper continued, “the gold died out, except for our golden fields of wheat. Then came World War Two. The Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. By 1942, the U. S. Army built the air force base at Great Falls and a satellite airfield here in Lewistown. Elevation 4167, latitude north 47 degrees, longitude west 109 degrees.

“They trained bomber squadrons on the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses and the top-secret Norden bomb sight—navigation, gunnery, bombing. They stored the Norden bomb sights here in a special concrete building with doors designed for bank vaults. The GIs trained here for three months and then they were sent to the European front to fly and die. They lost 548 bombers and shot down a thousand enemy aircraft. Squadrons trained in Montana dropped 71 tons of bombs over Leipzig, Oschersleben, Regensberg, Schweinfurt, Steyr, and Zwickau.

“Air force training lasted only twelve months here, after which the facilities reverted to a municipal airport, which we still enjoy.

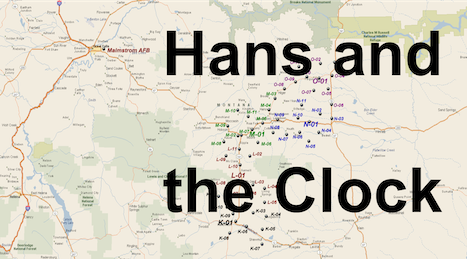

“Meanwhile, the wheat period continued until 1965, when the air force built two hundred intercontinental ballistic missile silos around the state, including the fifty that surround Lewistown. I call this the ICBM period. Our population peaked during the installation of the silos at under 7500, and has been declining since then. Today, I think, the military and federal wheat subsidies are the only reasons that this town survives.”

“The population curve resembles the path of an ICBM,” I said.

“Sadly,” said Mister Draper. “But it hasn’t reached its target yet.”

Flying

Mister Draper asked me, “May I ask, young man, what you are interested in?”

I didn’t want to talk about myself, so I told him that I was interested in flying, remembering that Miss Kate said he was a retired airplane mechanic. I said, “I find human-powered flight most appealing. Do you think someday that many people will have their own Gossamer Condors?”

Mister Draper said, “No, no. The physics are against it. Current prototypes require extraordinary athletes to power them. The smallest engines for ultralight aircraft generate twenty to twenty-five horse power. Why not go with ultralights?”

“Hmmmmm,” I murmured, “Are there ultralights in Lewistown?”

“Not at the airport. Not that I know of. They don’t need much of a runway so they could be used out in the country for fence reconnaissance or the like. Plenty of open land for emergency landings.”

“The air force wouldn’t be bothered by the presence of unregistered aircraft over the missile sites?”

“Oh. They can be extraordinarily sensitive, but they wouldn’t likely notice anything that small flying under two thousand feet altitude.”

“Not even a UFO?”

“No. If military radar were to catch a UFO, it would be flying over three thousand feet altitude.”

“But private planes have radar, don’t they? Did pilots ever ask you to check their equipment after they witnessed things in the sky that they couldn’t understand?”

“Yes, they have at that, but it had been other things malfunctioning, not the equipment.”

“So,” I asked, “you don’t believe in UFOs?”

Mister Draper said, “I am agnostic and I will likely remain agnostic unless a preponderance of irrefutable evidence attests to their existence. I mean their existence as physical flying vehicles.”

“You don’t doubt their existence as optical illusions or psychological delusions?”

“No, nor as electronic contusions. We have a preponderance of refutable evidence.”

Ellen

Uncle Walter and I caravanned from Chicago. Sometimes I followed his car, and sometimes he followed mine. My back seat was loaded with my fragile and valuable belongings, items that I hadn’t wanted to entrust to the haulage company, and those blocked my rear window, so I was happier to follow Uncle Walter, to be sure that he was still with me. We made the trip in two ten-hour days, taking one overnight at a motel in Fargo. For those two days, I was alone with my thoughts. I wasn’t sure what I was leaving, but I knew what I was headed towards; I had made the arrangements for a couple rooms at the Yogo Inn in Lewistown for a week, which I hoped would give us time to find permanent living accommodations.

But my friends, were they ever my friends? Jill, she was funny, wasn’t she? Betsy, always with something to say about what people were wearing, but what did she wear? And Peter, interested more in what was on the radio than in what others were talking about. Who were those people, anyway? Weren’t they more like the clerks in the grocery store, the grocery store where I never saw the same clerk twice? The neighborhood where I had lived for two years felt increasingly mythological the farther I got away from it. The faces, the things they wore, they way they talked, the apartments where they lived, they all kept reappearing in my thoughts, and every time they appeared they seemed more washed-out, more vague, more distant, more like pretend friends, pretend activities, things that happened in a pretend city. The museums, the ballet, the nightclubs, the grand stores, had they ever made me happy? Had Chicago ever felt like home? My apartment in Chicago was a crowded, noisy, and smelly play that I had attended, and now that its curtain had come down for the last time, I wondered how I had tolerated the place. It seemed foreign, strange, even hypothetical compared to the wind-swept, snow-covered plains that we were driving across. I began to feel that Chicago had been more threatening, more scary than I could ever have admitted when I was there. Why had I put up with it? What was wrong with me?

Uncle Walter, driving ahead of me on I-94 in his old Ford station wagon, Uncle Walter, just a tall lawyer in a herringbone jacket and silk tie, never having said a thing about himself in all the years that I had known him, Uncle Walter, never aging, never complaining, and never hesitating, Uncle Walter, always working, always able to attract wining cases and interesting clients, it seemed, without effort, Uncle Walter seemed more like family to me than my mother or father ever had, more reassuring, more stable, more thoughtful, and more kind.

Fragile china, made in China, that I had discovered at a thrift shop. A hat box with the hat that I had bought to wear to the ballet and that I may never wear again. My portable Olympia typewriter in its blue zippered case. A stack of prints in glass frames, prints of the streets of Paris, the trees of London, the markets of Mumbai, the beaches of Monte Carlo, places where I had never been. I had taken the prints down from the walls of an apartment in Chicago, a foreign apartment in a distant city.

But people in Lewistown were nice to us. They were nice to Uncle Walter; it’s always easy to be nice to Uncle Walter, the perfect kindly gentleman. But they were also nice to me, even though after two days on the road I didn’t look my best, or feel my best, or behave without irritation, pulling my heavy bag out of my trunk and dragging it into the lobby of the Yogo Inn off Main Street. Why didn’t I have a bag with wheels? Well, yes, the Yogo Inn didn’t seem to have a bell hop, but the clerk was nice. He smiled and he had everything ready. He was dark and spoke with a bit of a drawl. Did he get that from John Wayne movies? Would I like a room with morning light? No, and one key would do. He came around the counter himself and, without asking, picked up my bag and motioned with his head, “The elevator’s down that hall.” I was beginning to get suspicious, but, I thought, maybe this is the way they are supposed to behave in a small town like this. The clerk followed me into the elevator, and then pushed the button for the second floor. The place smelled clean, but not with the scent of cleaning products. The decor was modern, in hues of brown and gray. The room was open in a minute, my bag on a stand, and the clerk gave me a brief salute before closing the door. A badge on his jacket had said his name was Roy. No need to tip, I thought.

Uncle Walter hadn’t come straight to the inn, but had gone first to talk with Hans, who had moved to Lewistown only a month before. Hans had been staying at the new office while he looked for a place of his own. He had placed an offer on a house in town a week or two before we arrived. Uncle Walter also needed to get keys from Hans for the office. Uncle Walter called my room after he finally checked in and told me that everything was fine. “Good news,” he said. “Hans offer on the house closed in record time, and he will be moving over to it tomorrow. He’ll be able to get all his things out of storage.” I had been lying in my bed, unable to close my eyes, but Uncle Walter’s reassurance made me feel better. I wasn’t a strange woman in a strange town. Maybe the town wasn’t even strange. Maybe it was a place where good things could happen. But the darkness and the clean quiet air seemed strange. No flashing lights, no sirens, no roaring or clanking from the “L” rushing by. I raised my hand above me and it seemed like stone in the light from the bathroom nightlight. The light was strange. I didn’t know why. Maybe it was because this was a big change in my life. Maybe because I realized that here, in this small town, I could be the woman whom I had always wanted to be, a little less afraid, a little more confident, a little less vague, a little more distinctive, a little more proud, a little less subject to whatever came along, good or bad. I was going to make a good life for myself in this nice town.

Uncle Walter and I had breakfast in the morning at the Yogo Inn Hotel Restaurant. The main building used to be the Milwaukee Road train depot. Three stories of brick. Good thing there weren’t many earthquakes here. Breakfast of toast and fried eggs for the both of us, but I didn’t finish mine, the portion were so large. Uncle Walter and I had a lot to talk about. We went over our list of tasks to get the office ready. The haulage company was expected to arrive in two days. I didn’t get a vacation just to get settled myself, but Uncle Walter offered to walk over to the nearest realty with me; he had to check out the market, too.

Winter in Lewistown seemed no worse than winter in Chicago, without the piercing winds and taxis that try to run over you at intersections.

In the late morning, we walked five blocks down Main Street and used one of the keys that Hans had given Uncle Walter to open the front door of a pretty two-story brick building. Inside, we went room-by-room and I helped Uncle Walter decide what needed to be done to get the place suitable for our uses. The building was too big for only our offices, but Hans wanted space upstairs, and Uncle Walter wanted a large conference room where presentations could viewed by thirty people. Uncle Walter’s books and furniture could be stacked in any of the rooms in the back until we completed his office and library. I didn’t need to do the moving or installing things myself; instead, I acted as a general contractor; I arranged for the work and kept track of hours and what got done. Uncle Walter managed the paperwork. Fortunately, Hans had already got the phone line connected, so I called companies and their references for carpeting, curtains, woodworking, and painting from a card table and folding chair in the room nearest to the front door. I gave the estimates and bills to Uncle Walter. But enough of that.

Uncle Walter and Hans moved to Lewistown on the recommendation of the owners of a used bookstore on Main Street, Orville and Wilbur. “Tell me about your friends who own the bookstore here,” I asked Uncle Walter. “And are there other interesting people in Lewistown?” I got references from Orville and Wilbur for a plumber, painter, carpenter, and carpet guy. But even better, they knew everyone in town, so their introductions to the artists and craftspeople were great. Through Orville and Wilbur, it didn’t take long for us to become acquainted with the important people in town. Uncle Walter and I gave a standing invitation to Orville and Wilbur to bring interesting people to our office for cookies and coffee, and one or two of these meetings led to invitations to their places, and to see their work.

Aside from being a first-class administrative assistant, I have always had interests in the visual arts. Home decorating, costume design, masks, carving, pottery, painting, fine printing, sculpture, metal working. I think there wasn’t any area of the visual arts that I hadn’t had some familiarity with. That was the one advantage of living in Chicago, maybe not as good as New York, but still good. The museums and galleries. And I almost always left each show with a beautiful large volume that covered the work. These were the only things that left my apartment in Chicago in the care of the haulage company that I really cared about. Boxes of large books full of color and form. My boxes were combined with Uncle Walter’s and arrived two days after we did, brawny men with hand trucks unloading boxes from a big truck, piling them onto hand trucks, and pulling the stacks over the curb, through the building to fill up half a room in the back with box after box of books. That was great.

Finding an apartment wasn’t as hard as I thought it would be, and mine was only a few blocks from our office. Uncle Walter preferred to live in a house on a hill with a view, but I’d rather stay close. In Chicago, everything was close but always took a long time to get to. Here in Lewistown, I had the chance to keep everything I needed near to where I lived. And gradually the people at the grocery, the pharmacist, the beauty parlor, the gas station, became less like strangers and more like cousins. I made it a point to ask people’s names and to remember them. I asked about their families, their histories, where they had come from and where they wanted to go. Funny, it was about half and half. Half wanted to get out of Lewistown, out of Montana, and half wanted to stay; but they were all working out a way to make it possible, one way or the other. Half of them had a plan that made a little sense. I wondered whether, to them, my plan would seemed to make a little sense, or make little sense. I wasn’t sure that I had ever put it into words before. I wondered whether I had a plan that could be put simply into words.

Chapter 2. Hans

I miss the days when Halloween was a simple holiday

about making ritual sacrifices to evil spirits to ensure a plentiful harvest.

— Jimmy Kimmel, 27 October 2011

- Hans

- Acceptance

- A clock

- The passage of time

- Art and artists

- Distress

- Ten good men

- Lonely

- Provocateur

- An invitation

- Ellen

Hans

I had worked in used bookstores most of my life. Transitions bookstore in Lewistown was much the same as the other used bookstores everywhere else, so that it seemed familiar, and the people in the store also seemed familiar, except for Hans.

Hans was an odd duck, even compared to me or the flocks of oddities who tend to work in used bookstores.

Can I say what was odd about him? Was I a little disconnected from reality? Do I exaggerate? This is how it seemed to me.

Physically, Hans was not odd. He wore a plain white T-shirt, tan corduroys, and sneakers (not jogging shoes, but black Converse All-Stars with white soles and laces). His brown hair was barbered in a crew cut. His face was oval shaped and his eyes were blue. His fingers were long, but he was average height, maybe five foot nine. He seemed fit and strong, but not muscular or athletic.

His name was German but he didn’t speak with a German accent. I would say that his accent was more Californian.

His behavior was unusual.

When someone at the bookstore came to Hans with a question, such as whether we had a book on electric cars, or even French lace, he never checked the computer. He already knew the answer. He knew if we had a copy of a certain Agatha Christie “Tommy and Tuppence” mystery or Roosevelt’s history, and he knew exactly where it was in the store.

I knew others who could remember book locations. An attentive person picks up an impressive amount of detail while avoiding boredom during hours after hours of sorting, shelving, and cataloging. But Hans could seemingly effortlessly field any question, such as “When was the first Remington typewriter?” Or “Who was General Custer’s first lieutenant?” Or “Is there an Oldiluvium extrusion in the Judith Mountains?” (Sorry, I don’t know much about geology, so I just made that up.)

To support an answer to the next question, in the gaps between work at the bookstore, Hans was always reading something. He read quickly, turning through the pages of everything that came into his hands, I suspect, that he hadn’t seen before. I bet that Hans had read through the Lewistown phone book, cover to cover, and I knew that regular issues of the Lewistown News-Argus were no strangers to him.

Hans didn’t simply answer the question. If the questioner, young or old, was not looking at him, he waited. He looked the questioner in the eye. If they didn’t look back, he would say nothing but continue to look directly at the questioner. Eventually, the reluctant questioner would either murmur “sorry” and move away, or comply with Hans’s unspoken requirement. That settled, Hans would answer the question, followed by stating the title and author of the book in which the questioner could confirm the fact. Then Hans would say where the book could be found in our shop, or he would say, “We don’t have that book right now. If you leave your name and number, we will call you when we see it again.”

I once made the mistake of seeming to doubt something Hans said. I didn’t mean to. I was only astonished. A boy had taken a Zane Grey novel to the counter where Hans was on duty. The young man said, “I’m going to read every book he wrote.” Hans asked, “Do you know he wrote over ninety books, including eight books on fishing?” “Oh, yes,” said the boy. Hans nodded and smiled. He said “Charlie Russell illustrated one of his books.” Here’s where I stuck my foot in my mouth. I said, “Oh, really?” I had never heard that Russell illustrated Zane Grey. Hans gave me a cold stare. “I’m sorry.” I said. “I love the work of Charlie Russell.” It seemed that Hans had to think about it, but then he told the boy, “If you leave us your name and number or address, we can let you know when we get other books by Zane Grey.”

Another thing, too. Nothing surprised him. He was curious and had a curious confidence. It wasn’t his curiosity itself, or his accent, or his quietness, or his T-shirt and corduroys, or his crew cut, or the oval shape of his face, or his blue eyes, or his long fingers. These were ordinary enough. Maybe his ordinariness set him apart; maybe his ordinariness made him feel safe, or connected. He never seemed to worry; he was basically a happy quiet person. He didn’t shove it in your face. He didn’t need to.

To save money, Sally kept the bookstore cool, so I needed to wear a sweater at work. Sally was another case; she was always bundled up against the cold, as though it had nothing to do with the weather. Hans, however, wore nothing but corduroys, sneakers, and a T-shirt in the bookstore. When he got into the building, he took off his woolen gloves and leather bomber jacket and seemed perfectly comfortable.

Acceptance

The first day, I was surprised by the appearance of a hoard of kids and Hans reading a National Geographic to them, but this was not an unusual occurrence. People of all ages dropped into the store all the time, singly or in small clusters. They didn’t have to be looking for something, or selling anything, or holding a flyer for Sally to tape to the window or pin to the cork board by the door. They would drop in, often saying nothing, pick up a book or magazine, and plop down on an easy chair. Sometimes they would talk quietly. Sometimes one would close his eyes and nod off. No one was a stranger there.

Sally treated her employees strictly, but townspeople were never treated harshly. Employees were not allowed to eat anything in the main part of the store, not even chew gum, but townspeople would come in with their lunch bags and thermoses. Kids would be chewing gum. There was a bathroom in the back, and a small water fountain and a trash can beside the door to the bathroom. People would always clean up after themselves. If a child left a mess, sometimes I would see Hans clean it up and sometimes Sally would.

Except for one person, named Loren, if they were curious about me or Hans or Orville and Wilbur, they never showed it. If there were such a thing as midwestern reserve, then they had it. On the other hand, I wouldn’t regard them as shy, especially not the kids. The kids were demanding. They would come in and treat us like aunts or uncles, or like grandparents. “Do you have any Pippi Longstockings?” “Why do bees sting?” “How do flies fly?” and, if Hans weren’t there, “Where is Hans?”

The town’s artists also loved Hans. Eugene and Blanche were frequent visitors. Also three friends of theirs, Theodore Ellyson, George Kelly, and Paul Beck. Sometimes one or two would come in just to talk. Other times it was to talk about what they were doing and what they were wanting to find. This was because when Orville and Wilbur went out on a shopping expedition, they would also keep their eyes out for items of interest, which they sold to the artists at cost, as though it took no effort for them to find, buy, pack, or ship things to Lewistown.

A clock

Hans sat on the stool among piles of books behind the counter. He looked out the window. He did his job with normal efficiency. Keeping track of what we sold, making change, buying books that people brought in boxes, climbing ladders, on his knees to pull out the volumes that had been pushed behind, no one seemed interested in him, except for me and the kids.

But my curiosity had not even begun to be satisfied until mid October, when he told me that he was building a clock.

“What kind of clock? How is it driven?”

“Electricity, and it is made out of wood and bicycle parts.”

“Oh. With weights and a pendulum? How big is it?”

“It has a pendulum, yes, but no weights. The clock is big enough; it takes most of a wall.”

“Why build a clock? You can just buy one.”

“People build clocks,” he said. “Some do it to decorate a mantle, or to exercise their ingenuity.”

“But those are not your reasons,” I said (which is just like me, making unsubstantiated claims). “What does your clock do that any other clock wouldn’t do?”

“My clock will remind me of the passage of time.”

The passage of time

At Transition bookstore, some days passed like weeks, and other days like minutes, but I generally didn’t need to be reminded of the passage of time. A clock and a calendar were on the wall behind the counter, and a watch was on my wrist. I had plenty of reminders of the passage of time, not counting the lengthening shadows, and the shape of the light, and the growth of stubble on my chin. Temporal consciousness was not a problem for me. I’m young enough to fear my unknown future, and old enough to feel that I have wasted my life so far. I would rather forget about the passage of time, but it won’t leave me alone.

I wasn’t married; I didn’t even have a girlfriend who would marry me. Hans was about my age, and he also seemed unattached. Being alone didn’t seem to bother Hans, but it bothered me. I had a dead-end job. I lived in a boarding house where old Miss Kate treated everyone like a child. I didn’t even have many friends, at least no one near with whom I could share my feelings. I wrote fiction, but it was a lot easier for me to write it than to get it published. If I were hoping for money and fame from my writing, then I should turn myself into an asylum.

After college, my friends left for graduate school, or got married, or moved back to their home towns. I couldn’t move back to my home town. I didn’t have a home town. Even the cities where I had lived were not my home. So I buried myself in books.

A year before this, my sister had died; I have never felt more alone. They say that grief doesn’t last. One tribe of Native Americans had the “wiping of the tears” ceremony when a year had gone by. Now it had been over a year and, for me, it wasn’t any better.

It didn’t matter to me what work Sally gave me to do at Transitions. I was happy enough as long as I was busy. I was happy enough when people came into the store. It didn’t matter what their ages or what their reasons were. I was happy when Orville and Wilbur were working; they were always interesting. The hard times for me were the quiet times, when I could hear the echoes of every footstep.

Art and artists

The sewing machine that I had seen when I first walked into town was one of Eugene’s installations. More of his installations were scattered about town. On the eastern end of Main Street, just at the city line, was a billboard featuring life-size goldfinches made with tin cans arranged to fly in a spiral pattern toward and merging with a large yellow rose in the center. This was a collaboration of Eugene, Blanche, and Paul.

I asked Eugene what the sewing machine meant. He said, “It represents the soul. The human soul is a sewing machine left out in the cold, bound by a heavy chain to a light pole.”

I asked Eugene what the swirling goldfinches on the billboard meant. He said, “They represent the soul, the golden flower of enlightenment. But they’re nailed to a board and left out in the weather, winter and summer.”

I said, “You’re pulling my leg, right? Everything doesn’t represent the soul.”

Eugene said, “You’ll see. You should come over tonight. We’ve plenty more works of art about the house. And I think Theodore will be there. Come over after work and we’ll feed you.” Eugene gave me a big smile. “It would be good for your soul.”

I found that focusing on others made my heart feel lighter. Maybe the sewing machine and the swirling goldfinches represented the heart. I needed to reread Jung.

It turns out that Eugene and Blanche’s house was out Third Avenue a block from Miss Kate’s boarding house. After work, I went home and went into the sitting room for an old newspaper from a basket. In my room, I got my bag down from the shelf above the closet, and I rolled up in the newspaper my parents’ pewter candlesticks.

Eugene and Blanche lived in the Symmes house. Ahem. The Symmes mansion. It was set behind a beautiful blue spruce decorated by the weather with snow and ice cycles like a Christmas tree for a giant.

I knocked on the door with the candlesticks under my left arm. Blanche answered right away, saying “I saw you coming. Goodness. Come in quickly; it’s cold out there.”

Blanche was dressed in a bright yellow dress cut from an eighteenth-century pattern, with yellow lace and puffy yellow shoulders. In contrast, her red hair was on fire. Drop your coat and things on that chair. Gene and Ted are drinking brandy in the library.”

I had my mouth open. She said, “Oh, this. Sorry. Ted needed a model to wear this. He’s already taken photographs. I think it was a wedding dress; he dyed it. It’s coming right off.” She smiled. “This way, please.”

The place was beautiful, with parquet floors, cherry-wood moldings and wainscoting, alabaster sconces, and marble steps on a grand staircase ascending from the foyer. But artworks were hung and leaning on every vertical surface, photographs, paintings, most without frames, collages, papier-maché statuettes, and many small things glued into old orange crates and wooden soda boxes.

I put the candlesticks on the chair with my coat, hat, scarf, and gloves.

Blanche led me past the stairs to the left toward the back of the place. She said, “I know it looks like a mess, but it grows on you. Eugene says that the way for an artist to avoid becoming attached to his work, so he can sell it, is to make lots of it. Others say just make it ugly.” She laughed as she opened the library door.

The library, too, was full of artworks, mainly sculptural. A man in blue overalls with erratic blonde hair and a stubble of beard raised his eyes from his glass of brandy, looked at Blanche, and said, “Ah, here’s our model of yellow perfection!” He smiled.

Blanche curtsied and said, “A recently hatched chick may be perfect, too, but in time it molts.” She left me with Ted and Eugene.

Ted looked at me and said, “Ted. Glad to meet you.”

A gray cat meowed, jumped off a chair, and ran past me through the door.

Eugene offered me a brandy, which I accepted. After Eugene gave me my glass and I had a sip, he said, “Thanks for coming over. I made dinner tonight; I hope you’ll like it.” With a more serious expression, he said, “Lewistown is far from the thick of civilization; I hope that the town hasn’t been getting you down.”

“The same,” I said, “for you. How do you survive as artists here?”

“Ah,” he said. “I have outlets in New York and in L.A., but mainly I praise my dearly departed Aunt Bessica, whose dearly departed husband, Uncle Hugh, left her with more money than she could spend, and a love of art.”

“Yes, but why Lewistown?”

Ted answered, “Why Lewistown? It’s remote from the arts scene, it has dreadfully long and dreadful winters, and its native population is provincial, but it’s cheap to live here. No one bothers us. Isolation and cruel winters drive artists inward, where we either find our souls or go mad.”

“Sheesh,” I said. “I think I’d rather be driven outward.”

“Fortunately,” said Eugene, “we’re not entirely alone.”

“As for that,” I said, “thank you for inviting me tonight. I love all the clutter; lots of interesting things to look at.”

Eugene said, “The house decor is complex but the meal will be simple. Come this way . . . to the kitchen!”

Eugene led Ted and me to the kitchen, where we found Blanche, dressed in blue jeans and blouse, stirring something in a big pot.

Eugene said, “It’s a bouillabaisse.”

I said, “You get fresh seafood in the frozen north?”

Eugene replied, “No, Sorry. It’s all been frozen, but I hope it tastes good. Probably just a little more chewy.”

Ted and I took a peek into the pot, while Eugene went into the dining room and started cutting a large loaf of bread.

I said, “Wait a second, I have something to add to the table.” I went back into the hall and grabbed the candle sticks, still rolled up in newspaper.

Everyone else was standing behind a chair around the dining-room table. I said, “I didn’t bring a bottle of wine, as would be customary, but I would like you to have these.” I handed the bundle to Blanche, who unrolled the candlesticks.

Blanche said, “These are lovely.”

Eugene said, “Oh, something practical!”

I said, “Those were my parents’. Candles, you know, represent the soul.”

Eugene said, “The sticks themselves are only lifeless bodies, but we can put candles in them, light them up, and remember those to whom we were once close. Thank you.”

Blanche pulled out a pair of white candles and a book of matches from the buffet, stuck them into the pewter sticks, and lit the candles. Their yellow light warmed up the table and gave an extra glow to each cheek, an extra glint to each eye.

The bouillabaisse was warm and tasty, and the bread moist and chewy. Eugene said, “I baked that bread.” Everyone complimented him on the yeasty result.

We all sat and enjoyed the soup, along with a bottle of cheap Côtes du Rhône.

I asked Ted, “What are you doing with photos of Blanche in the yellow wedding dress?”

Ted said, “I am working up several ideas. One is a parody of Cinderella fairy-tale romance. Another is an invasion of clowns in old wedding dresses, all in beautiful pastels. They come down from the altars of synagogues, churches, and mosques, and they try to entertain our children, but our parents will have none of it. The clowns seem to lack sincerity. They have a sense of humor but no sincerity.”

Blanche objected, “You wouldn’t put a clown’s makeup on my face, would you?”

Ted said, “That’s only one of many ideas. For your face, I am thinking of an invasion of angels in wedding dresses. They come down and taunt our elders. They entice our young like a hoard of pied pipers.”

Blanche smiled mischievously and wagged a mocking finger at Eugene.

Eugene said, “Well, just because I’m older than you is no reason to gloat.”

Ted said, “Aha!”

Eugene turned to me and said, “We have so many questions for you. Where are you from? What do you do? Why did you come to Lewistown, Montana? Did you know someone here? Do you plan to stay long? How is it to work with Hans? How is it to work with Sally?“

Blanche said, “Yes, isn’t Sally like an invading angel?”

“Exactly like an invading angel,” I said, “but one who was educated in the eighteenth century. Not a bad century for invading angels, but . . . ”

Ted added, “But Sally belongs here more than we do. We are all transplants from foreign lands. New York, Los Angeles . . .”

I said, “I am a transplant from New London, Connecticut, and the twentieth century. I write fiction, and have worked in used bookstores from Connecticut to New Jersey.”

Ted said, “So then your stint here at Orville and Wilbur’s Transition is not a transition from a non-bookstore career. You are here only to gather material for your next novel, right?”

“No,” I said, “I am in a transition only from a lonely life to this happy company. I’m seriously getting away from it all.”

Eugene said, “But we are not all here. Next time, you should meet Paul. He makes those kinetic sculptures driven by wind, weights, or falling balls. He’s a useful man to have around.”

When we had finished the soup, and wine, and bread, Eugene said, “Leave the dishes.” Eugene turned to Blanche and asked, “Isn’t Anna here tomorrow? She can clean things up.”

I had a great time, but the teasing banter between Ted and Blanche reminded me of my sister, Bonnie, and made me feel more isolated than I should have thought. I went back to my room that night with a lot on my mind.

Distress

Hans seemed to enjoy his privacy. He did not volunteer personal information, nor did he ask for it from others. But I realized that he had a keen interest in the lives of the people around him, including me.

One day, a friend of Sally’s came into the bookstore. Anna was tall and overweight. I think she was the house cleaner for Eugene and Blanche. Her cheeks were always flushed like a caricature of a Scandinavian maiden, but Anna’s maiden years were years gone. Anna looked around, craning her neck. I asked her, “Could I help you find anything?”

She wasn’t looking for a book. She asked, “Where is Sally?”

I nodded toward the biography section in back. Anna darted back there. Hans was at the register, that is, at the computer that we used to track inventory. Both of us could hear much of the conversation.

“He did it! Barney quit!”

“He what? Why’d he do that?”

“He said they didn’t treat him right. He’s been angry since the masons refused to let him join their men’s club. He’s been pretending to go to work every day for weeks because he was afraid to tell me. Come to find out he’s been spending his days at the tavern. He has his own men’s club at the tavern, though the dues are higher.”

“What did you expect? He’s an overgrown child. You don’t have to put up with that. You should just kick him out.”

“I couldn’t do that. Where would he go?”

“Let him sponge off his drinking buddies. He won’t get anything from me. That’s for sure.”

I noticed that Hans’s eyebrows were up. But Anna and Sally must have realized that they were being overheard, because they lowered their voices and moved to the lunchroom in the back. Everything was very still in the bookstore. Overheard, on our high ceilings, ceiling fans slowly turned.

After Anna had left, I went by the counter and whispered to Hans, “Living alone may be lonely, but it lowers one’s risk of suffering the inconsiderations of others.”

Hans whispered, “I feel sorry for both Anna and Barney.”

I whispered, “Well, I do, too. I’m not taking sides. It’s too hard to decide whether in my life I have acted more like Anna or more like Barney.”

Hans whispered, “It is too hard to be perfect.”

Ten good men

After overhearing Anna’s exchange with Sally at the bookstore, I asked Mister Draper, during dinner at the boarding house, how many men were members of his masonic lodge, and whether he sometimes met with them elsewhere in town.

Mister Draper said, “God offered Abraham to save Sodom if Abraham could find ten good men in it. We have over a dozen, although half are getting on in age and are not active.”

“Can you tell me who they are, or do I need to look for men with masonic pins on their lapels?”

“I could tell you, but what would you do with the information? I’ll tell you this. I understand that you work with Hans at the bookstore. Hans is a Freemason in good standing, although not a brother of our lodge.”

“How did you learn that?”

“I saw him leaving our lodge once, so later I asked our grand secretary, who had been there when Hans visited.”

I said, “I heard that you haven’t accepted everyone who applies for membership, one Barney in particular.”

“No. Barney is a sad case. He is a good man with a weak character and a weak mind. A sad case. One wonders what kind of help he needs.”

Lonely

I was lonely. To distract myself, I read a lot. It was a good thing I worked in a used bookstore. I got Sally’s permission to borrow books. “No more than three at a time,” she said. I looked for classical American literature set in the west.

I read The Octopus by Frank Norris, a bleak and tragic epic of the conflict between the wheat farmer and the railroad barons in the central valley of California. The sheep are run over by the train and the wheat farmer doesn’t have a chance.

I read Zane Grey’s Desert of Wheat, although I could barely tolerate the manly confusion of Kurt Dorn who loves growing wheat with a religious fervor, or the idealized innocence of Lenore (“I wonder—how I will feel—when I see him—again.... Oh, I wonder!”). Matching this romance, this being set in the Pacific Northwest during the first world war, Grey works out the drama between the stereotyped wheat farmers, the stereotyped bankers, and the evil, unprincipled stereotyped representatives of the International Workers of the World, said to be in the payroll of imperialistic Germany intent on destroying the ability of the Americans to feed the allied armies fighting in Europe.

I read The Big Sky by A. B. Guthrie. I was not impressed with Boone Caudill’s crude sense of right and wrong. I hoped that it didn’t represent Montanans, even though the state called itself the Big Sky Country.

I read Charlie Russell’s stories, Rawhide Stories and Trails Plowed Under, both sequences of yarns and tall tales concerning interesting characters such as Pat Geyser, who built a resort out of cottonwood logs that shrunk up so much in the dry weather that Pat could move the hotel in a wheel barrow, and Morman Zeke, who was an Indian trader and a brawler. It also tells a story about a “hoss-wrangler” who thought he was a good cook and who became a leading citizen of Lewistown after he had to leave Landusky for making a pudding for Thanksgiving that killed three guests and disabled several more.

I started reading all the B. M. Bower that I could find, starting with Chip, Of the Flying U because Charlie Russell illustrated it. Chip’s story would be a reserved romance set in Chouteau County except that Chip, an unschooled ranch hand turns out to be able to paint so well that men can see the cows on his canvases breathe and bellow.

I reread The Call of the Wild. Its inversion of the civilized and the brutish appealed more to me then than it had in my youth.

I read many traditional westerns, books by Zane Grey, Louis L’Amour, Bret Harte, Larry McMurtry, Monty Walsh, and anything else that I found at the store.

I tried taking walks around town, but the weather made me shorten this exercise to where it wasn’t much help. I spent time in the library. At least in the library there were other people with a love of books. I began to fantasize about the younger female librarians, but this made me feel my age and my isolation more acutely. I was not cut out for being happy only in my fantasies.

Halloween was soon announced in the store windows of the town. Sally brought forward all the books that she could find in the store on saints, witches, the occult, and the macabre, including all our books by Edgar Allen Poe. She decorated the window display and the table by the counter with these items, with black and orange crepe paper, and with a couple plastic skeletons that she kept in a closet.

In Lewistown the merchants do something special for young trick-or-treaters on the Sunday before Halloween. Mothers and fathers usher their kids in their costumes from store to store. There wouldn’t be enough theme books in the appropriate age range in the bookstore, so Sally had a basket of black liquorice and jawbreakers shaped like skulls at the register.

I was in no mood to dress in costume for work. Fortunately, Sally did not ask me to, although she came to work in a calico apron and hat. Hans also wore only his usual clothes, although when kids came into the store, he put on a huge smile.

Provocateur

Loren was the one adult who did not conform to the general nature of acting reserved during his visits to the bookstore. He was skinny and short but walked like a tall man, with his arms swinging. His face was pimpled, but he was at least a few years beyond high-school. I think he worked at the Central Montana Coop just north of town on Highway 191.

Loren would lope through the door and head straight for the counter. He would doff his cowboy hat, put his elbow down, tilt his head to the right, and say anything that would pop into his head, especially if seemed to him to be provocative. My role was to keep a straight face, trying not to directly encourage him, because what seemed to him to be provocative usually seemed to me to be funny.

Once Loren asked, “Does it always smell like this?” I replied, “Like what?” He said, “Like a person would notice it.” I said, “Definitely not. If a person would notice it, then it’s not what he’s used to.”

Days later, Loren said, “You’re not from around here. Do we, the good people of Lewistown, seem like aliens, or just poor imitations of what you find elsewhere?’ I tried to think of a witty reply, but said only that I thought that most people were the same everywhere.

He said, “I think my nose is clogged up with wheat dust.” “I hope that’s whole wheat,” I said, thinking that I shouldn’t have said anything. “I think whole wheat isn’t as good for you when it’s mixed with mouse-turd dust.”

Once Loren asked, “Where can a man think?” I looked him up and down and said, “Some people do it in the road.” “Not in this town,” he said.