Tom Sharp

linguistics

|

Sharpεn

English iz a funny langwich. Ain’t it true. In Sharpεn, se εsud mez: Ynglish εs a langakt apɘrais; εs nop le tru. But woodn’t any nachurel langwich bee, after funny peepel mess with it for centuryz? But εsud nop εny langakt nachis, aftɘr mεs εsεn wid le for andozyrez humz apɘrais? Its defects give it depth and charm. Giv dypis e charm tu le dyfεt leo. Its low information density gives it resilience to noise. Giv fortyk-noyz tu le dεns-informshɘn lo leo. Its irregularity makes you think you couldn’t do worse. Kaz dink εsakt de dat kyut εsud nop bad mor de regulisnoakt leo. Certainly its spellyng cood bee improovd, its word-order normalized. Sɘrtanky, amεnd εskul spεlakt leo, mek εshun rεgulis ord-mot leo, And straightening out those irregular verbs would be a service to humanity! ¡E rεktyn εsεnt dyz vεrbz rεgulisnop εsun a sεrvis tu humshɘn! With all theez changez, it’d be another langwich altoogether, and it’d be a useless language if people didn’t love it so.

The longest sentence written in Sharpεn so far

Kog a tym, wεn εskog εsud nachis dinz dat εsεd yzy nop, thru studact asidua, horaz ɘv provo e εror, gin e tydis, dεn sumyn εsud a sy ɘv rylyf Sharp Tam.

About Sharpεn

- I, the poet Tom Sharp, began to develop the constructed language Sharpεn in February 2018 after writing about international auxiliary languages. See International auxiliary language.

- Sharpεn has these design principles:

- It is designed to be likeable by poets and music composers. Numbers, pronouns, days of the week, months, and planets are based on solfège.

- It has no dipthongs.

- It is phonetic. It has no ambiguous pronunciations.

- It is regular.

- It is atonal except for distinguishing a question from a declaration.

- It is non-sexist. Its personal pronouns do not express gender.

- Its lexicon is chosen to be common, short, distinct, simple to pronounce, and compounded from simpler terms when the meaning can be made obvious. Sunday = Dy (day) + zyit (zeroth).

- Sharpεn orthography avoids ambiguities. Each character or character has only one possible sound and is not modified by context or by adjacent sounds. Its phonology is simplified American English, and pronunciation is strictly phonetic. Word accent falls on the vowel after the first consonant; therefore, on the first syllable of Sharpεn.

- Nobody speaks Sharpεn, although it is designed to be spoken or sung.

- I have named Sharpεn to honor my father, Frederick James Sharp. When I and my three siblings were young, to entertain us on car trips, Dad encouraged us to make up our own language, and developed it with us. We five Sharps abandoned the development of this proto-Sharpεn after my mother became irritated that she could not understand us.

-

I have several other reasons for making a language from scratch:

- I enjoy the challenge of doing difficult things.

- Linguistics is a good science to learn.

- Conlanging is an art, giving opportunity for creativity and playfulness.

- I think it will be fun to see what translations of poetry and song lyrics into Sharpεn will look like.

Orthography

- Sharpεnis orthography is a subset of ISO Latin without diacritics, in which ambiguities are eliminated, supplemented by IPA symbols for two vowels:

- There are no silent letters (such as the gh in “though” in English). No two graphs or digraphs make the same sound (such as c and s, or f and ph in English).

- Here is the Sharpεn alphabet in alphabetical order, upper and lower case:

- Aa, Bb, Cc, Dd, Ee, Xε, Ff, Gg, Hh, Ii, Jj, Kk, Ll, Mm, Nn, Oo, Pp, Rr, Ss, Tt, Əɘ, Uu, Vv, Ww, Yy, Zz

- Sharpεn uses X as a capital letter form for ε, epsilon. X is not, in itself a letter in Sharpεn. Capital epsilon is merely typed as X; if you are writing it by hand, then just make your epsilon full height.

- Three of these characters are not on your keyboard. For ease of typing, Sharpεn permits doubling of the related vowels, as follows:

-

X EE (for a capital Epsilon) ɛ ee Unicode 025B, Entity ɛ or ε Ə UU Unicode 018F ɘ uu Unicode 0258 - With the alternate digraphs, Sharpεn is typed “Sharpeen.”

- Sharpεn does not have phonemes for Q or X.

- Sharpεn punctuation is the same as in American English, except as follows:

-

- Interrogative and explanatory sentences end with the normal question marks and exclamation point, and begin with inverted question marks and exclamation points, as in Spanish:

- Inverted question mark: ¿ – Unicode 00BF, HTML entity ¿

- Inverted exclamation point: ¡ – Unicode 00A1, HTML entity ¡

- In English, compound nouns and adjectives are usually not hyphenated unless they would cause confusion. In Sharpεn, compounds are always hyphenated.

- In English, we say “word order.” In Sharpεn, we say ord-mot.

- In English, proper nouns and adjectives derived from them are capitalized; in Sharpεn, proper nouns are capitalized but not other parts of speech derived from them. In Sharpεn, the words gad and kryst are not considered proper nouns so are not capitalized.

- In Sharpεn, we do use contractions, but not as a formal part of the language. In informal speech, all kinds of ellisions may be made.

- In Sharpεn, we prefer the Oxford comma.

Phonology

- Unlike English:

- Sharpεn is a phonetic language.

- Sharpεn has no dipthongs.

- Sharpεn does not feature vowel reduction in unstressed syllables (where the vowel is reduced to a schwa).

- Otherwise, Sharpεn phonology is a simplfied version of English.

Vowels

- Sharpεn has eight vowels, described in the table below using the IPA alphabet classifications: close to open, and high to back. In the table cells that contains a Sharpεnis vowel, the format is “x /y/ zee,” where the x is the Sharpεnis vowel, /y/ is the IPA symbol for its sound, and zee is a word pronounced in English/American with the intended sound.

- To make Sharpεn work phonetically, that is,

where each vowel has only one phoneme regardless of context, Sharpεn borrows

characters from the IPA alphabet:

- ε, the epsilon sounding like the e in set

- ɘ, the schwa for the sound like the u in suck

- a, the script-a sounding like the o in sot

- Sharpεn avoids dipthong vowels, which are common in English. It has no sound O as in now, A as in wade, or I as in the first-person singular personal pronoun or the word “side.”

-

High Near-front Central Near-back Back Close y /i/ see u /u/ soon Near-close i /ɪ/ sit o /o/ soak Close-mid e /e/ say Mid Open-mid ε /ε/ set ɘ /ʌ/ suck Near-open Open a /a/ sat a /ɑ/ sot - Each of these vowels has a capital equivalent:

- Here are the eight Sharpεn vowels in alphabetical order, upper and lower case:

- Aa, Ee, Xε, Ii, Oo, Əɘ, Uu, Yy

- In Sharpεn, vowels are never combined; they are always pronounced separately. For example, “again” zay is pronounced with two syllables, soundling like “zah-ee.”

- Read on to see how Sharpεn names these vowels.

Consonants

- In Sharpεn, as in English, all consonants are pulmonic; that is, their production depends on the speaker forcing air from the lungs.

- A few consonants are not spelled or do not sound as they do in English.

- Sharpεn has no nasal-velar N; it doesn’t use the +ing suffix to construct a gerund.

- Letter C is always combined with H in Sharpεn for the Ch /t͡ʃ/ sound, as in the English “church.” C is never pronounced like K or S.

- Our G is always hard.

- Sharpεn spells the post-alveolar sound as in English “judge” with GH. In Sharpεn, “judge” would be spelled ghugh. GH is never silent nor pronounced like F.

- The voiced palatal approximant J /j/ is always combined with a vowel in Sharpεn. “Yes” in English would be spelled jεs in Sharpεn; “use” in English would be spelled juz in Sharpεn;

- The consonant H modifies the sounds of five consonants to make digraphs:

- The following consonants are pronounced exactly the same in Sharpεn as in English:

- B, D, F, H, K, L, M, N, P, R, S, T, V, W, Z

- In the table cells below that contains a Sharpεnis consonant, the format is “x /y/ zee,” where the x is the Sharpεnis consonant, /y/ is the IPA symbol for its sound, and zee is a word pronounced in English with the intended sound.

-

Labial Dental Alveolar Post-alveolar Palatal Velar Glottal Nasal m /m/ mom n /n/ none Plosive/

affricatefortis p /p/ pup t /t/ tat ch /t͡ʃ/ church k /k/ kick lenis b /b/ bob d /d/ dud gh /d͡ʒ/ judge g /g/ gag Fricative fortis f /f/ fluff th /θ/ thin s /s/ sass sh /ʃ/ shush h /h/ hah lenis v /v/ valve dh /ð/ then z /z/ zoo zh /ʒ/ vision Approximant l /l/ lull r /r/ roar j /j/ yay w /w/ wow - In English, the letter S is sometimes unvoiced and sometimes voiced like the letter Z. In Sharpεn, s is always unvoiced and z is used where it would be natural for an English-speaker to voice an alveolar fricative. For example, in Sharpεn the suffixes +izm and +ist, which add the meanings “practice of” and “one who practices”, have different middle letters.

Names of the letters

- The Sharpεnis noun for upper-case or capital is prap. Its adjectival form is prapis. This adjective should be compounded when giving a capital letter name. Capital M in Sharpεn is prapis-M. The Sharpεnis noun for lower-case or minuscule letter is minusk Its adjectival form is minuskis.

- Sharpεn for name is nem (pronounced the same as the English “name”).

- Sharpεn for “pronunciation hint” is pronans hint. The word hint is the same as in English.

- The names of all Sharpεn letters contain the letter L. L precedes the vowels and εl follows the consonants:

-

Prap Minusk Nem Pronans hint A a Prapis-La, la /a/ as in allow B b Prapis-Bεl, bεl /b/ as in bell C c Prapis-Cεl, cεl /t͡ʃ/ as in check D d Prapis-Dεl, dεl /d/ as in dell E e Prapis-Le, le /e/ as in late X ε Prapis-Lε, lε /ʌ/ as in led F f Prapis-Fεl, fεl /f/ as in fell G g Prapis-Gεl, gεl /g/ as in geld H h Prapis-Hεl, hεl /h/ as in hell I i Prapis-Li, li /ɪ/ as in lid J j Prapis-Jεl, jεl /j/ as in yell K k Prapis-Kεl, kεl /k/ as in Kelly L l Prapis-Lεl, lεl /l/ as in let M m Prapis-Mεl, mεl /m/ as in pell-mell N n Prapis-Nεl, nεl /n/ as in Nell O o Prapis-Lo, lo /o/ as in low P p Prapis-Pεl, pεl /p/ as in pell-mell R r Prapis-Rεl, rεl /r/ as in rebel S s Prapis-Sεl, sεl /s/ as in sell T t Prapis-Tεl, tεl /t/ as in tell Ə ɘ Prapis-Lɘ, lɘ /ʌ/ as in luck U u Prapis-Lu, lu /u/ as in loon V v Prapis-Vεl, vεl /v/ as in develop W w Prapis-Wεl, wεl /w/ as in well Y y Prapis-Ly, ly /i/ as in lee Z z Prapis-Zεl, zεl /z/ as in zealous - In addition to single letters, the names of six Sharpεnis phonemes written with digraphs of the letter H, are compound consonants:

-

Prap Minusk Nem Pronans hint Ch ch Prapis-Cεl-hεl, cεl-hεl /t͡ʃ/ as in church Gh gh Prapis-Gεl-hεl, gεl-hεl /d͡ʒ/ as in judge Sh sh Prapis-Sεl-hεl, sεl-hεl /ʃ/ as in shell Th th Prapis-Tεl-hεl, tεl-hεl /θ/ as in thin Dh th Prapis-Dεl-hεl, dεl-hεl /ð/ as in then Zh zh Prapis-Zεl-hεl, zεl-hεl /ʒ/ as in vision

Stress

- Stress of multiple-syllabic words in Sharpεn falls on the vowel after the first consonant.

- We say Shárpεn, not Sharpέn.

- We say húmmεmis, not hummέmis.

- Because Shárpεn uses no prefixes, the stress isn’t likely to change when forming an adverb from a verb, or an adjective from a noun.

- Compound words are stressed on each part, although the first part should have the strongest stress. For “starlight” we say lýt-saˌr.

- Words with more than three syllables can have a secondary stress on the second syllable after the primary stress, such as límitnoˌpshɘn.

- An exception to this is for words whose root begins with a stressed vowel, and for proper names that begin with a stressed vowel.

- We say Ýnglish, not Ynglísh.

- Vowels in unstressed syllables in Sharpεn get their full sounds; they are not pronounced as schwas (as in English).

Vocabulary

- Because Sharpεn is phonetic, it has no homonyms. In English, toe and tow are different words that are pronounced the same, /to/, but are distinguishable in usage. However, both would be spelled the same in Sharpεn, to, so we do not use this sound for more than one word. This is true also of nouns that sound like corresponding verbs in English, such as the noun “light” and the verb “light.” In Sharpεn, one is formed from the other by a suffix. “Lyt” is the noun, and “lytyn” is the verb.

- This is different from saying that a word in Sharpεn can have only one meaning. As in English, the meaning of a word can be expanded when it is given a metaphorical usage. English has gone overboard with multiple meanings for the same words. We read a book left to right, and we book a criminal after reading him his rights.

- To see what words are already defined, open the English-Sharpen.html file, or use the Sharpεn lexical lookup.

Rules for forming words

- In general, Sharpεn prefers to derive a word from existing roots instead of to borrow or to coin. It puts two words together, such as “time” and “span” for span-tym, or adds an adverb or preposition such as adding aft to lyf meaning “afterlife.”

- The second word in a compound in Sharpεn always modifies the first word. “Afterlife” in Sharpεn is lyfaft, not “aftlyf.”

- A compound may be hyphenated. For example, sar is star, and lyt is light, so lyt-sar is starlight. However, compounds do not need to be hyphenated. The two roots movɘr and se are not hyphenated in movɘrse meaning “automaton” or “self mover.”

- In Sharpεn, suffixes are added to form new words.

-

- Form an adjective from a noun:

- +is – process or state of. For example, something like Sharpεn is Sharpεnis (adjective formed from a noun).

- +fɘl – full of.

- +lεs – being without.

- Form an adverb from an adjective:

- +ky – in the manner of. For example, wise is wyza, so wisely is wyzaky.

- Form a verb from an adjective or noun:

- +yn – to use as or make so. For example, piano, the instrument, is pyanan, so pyananyn is playing a piano. Again, “straight” is rεkt so “straighten” is rεktyn. [My current practice is that +yn verbifies any noun. Example: “show” - sho:n, shoyn:v. This practice could be refined.]

- Form a noun from a verb by adding various suffixes:

- +akt – the act of. For example, ad is to add, so adakt is the act of adding.

- +shɘn – the state, condition, quality, action, process, or result of. For example, inform is to inform, so informshɘn is the result of informing.

- +ab – object of. For example, “see” is sy, so syab is a sight to be seen.

- +ɘr – the doer of. For example, adɘr is a person or thing that adds.

- +ebɘl – ability to. For example, adebɘl is addability.

- +filo. – lover of. For example, adfilo is one who loves to add.

- +fobo – hater of. For example, adfobo is one who hates to add.

- +lok – location of. For example, zu is to dwell, so zuloc is a dwelling.

- Modify a verb:

- +mis – poorly, wrongly. For example, “head” is hεd, “lead” is hεdyn, and “mislead” is hεdynmis.

- +nop – opposite of. For example, “approve” is pruva, and “disapprove” is pruvanop.

- +wid – same as. For example, “pose” is post, and “support” is postwid.

- Modify a noun:

- +εt – little, diminutive. For example, “pen” is fεd so “pencil” is fεdεt.

- +ity – the quality of. For example, “sexual” is sεkis so “sexuality” is sεkisity.

- +izm – the advocation or practice of. For example, “manualism,” the practice of making music with one’s hands, is manizm.

- +ist – one who advocates or makes a practice of. For example, “manualist,” one who makes music with one’s hands, is manist.

- Modify an adjective:

- +ish – weaker.

- +mor – stronger.

- +max – to the max.

- +min – in the least.

- +fɘl – surfeit.

- +lak – lack, being without.

- +nop – opposite or negation of. For example, “good” is gud, so “not good” is gudnop.

- In Sharpεn, consonants are not doubled to maintain the sound of the preceding vowel, as in English “hit” and “hitting.” This is because a vowel in Sharpεn represents only one phoneme. Therefore, when compounding roots that end and begin with the same letter, Sharpεn lets us reduce the double to a single. For example, “human” is hum and “male” is mεm, but “man” is humεm, not “hummεm.” Again, “transportation” is port + trans + shɘn, but this is spelled portranshɘn.

- Adding suffixes to this nouns provide adjectives, adverbs, and verbs. “Manly” is humεmis as an adjective, and humεmyk as an adverb. “He mans the boat” in Sharpεn is Humεmyn da bot le.

- Verbs do not have suffixes that can be expressed with a conditional or modal auxiliary of the verb “to be.” These encapsulate time, completion, progression, possibility, permission, condition, and obligation. Therefore, for example, Sharpεn does not include a verbal suffix expressing possibility.

- When a Sharpεnis word is not available, use Unish, but transpose it to Sharpεnis phonemes. The previous sentence written with Sharpεn phonemes is Wεn Sharpεn vokabjulery yz nat avelabul, juz Yunish, but with Sharpεn fonyms. This sounds somewhat like the original, but with an accent, but is not a sentence in Sharpεn because it doesn’t follow Sharpεn grammatical rules.

- Here are rules for finding new words for Sharpεn:

- Find a Unish word only if a Sharpεn word hasn’t been identified, and if an obvious and simple Sharpεn word can be formed from existing roots with a suffix or compound. Etymologies are useful; for example, “desire” is from Latin “from + star” so that the Sharpεn word is sar + frɘm.

- Look up the word

using the Unish dictionary search at

http://www.unish.net/search/e_unish_Dic_Search.jsp. - Transpose the Unish word into Sharpεn phonemes.

- Drop any letters of suffixes that are particular to Sharpεn.

- If there are two acceptable words in Unish, choose the shorter one. If both are the same length, choose the one ending in a vowel.

- If the word is not unique in Sharpεn or if its use would be an irregularity (such a noun as looking like a plural), choose something else, or alter it to make it unique.

- Go to Esperanto or the next language given written in Latin letters in the Unish dictionary search if the words that Unish chooses are not unique or not suitable in Sharpεn.

- Start with the Esperanto if Unish doesn’t have the word.

- You may shorten and respell for consistency and esthetics, and to avoid nouns ending in s or z.

- When the above doesn’t work, make something up to be distinct from other words in Sharpεn.

- For example, lacking a word for “bird,” Unish gives “tori/birdo” (borrowing either from the Japanese or from the Esperanto). Transposed, these would be “tory/birdo”. Choosing the shorter, we get this Sharpεnis word for “bird”: tory.

- Similarly, the Unish word for “because” is koz, which looks like a plural in Sharpεn, so we drop the z to form the Sharpεn word ko.

Loan words

- Some statements will not be clear without using a loanword, but please drop any diacritic if it is doesn’t maintain a necessary distinction.

- Proper names are kinds of loan words, but these should be spelled with Sharpεnis phonemes and reordered. In Sharpεn, last names are first, and first names are last. My father’s name in Sharpεn, is Sharp Ghemz Frεdɘrik.

Numbers and things

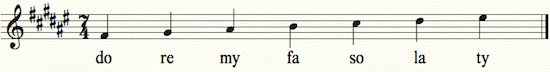

- Cardinal and ordinal numbers, planet names, months, and days of the week start with the Sharpεn version of solfège, which are also the names of the scale degrees of movable do solfège. These have the same sounds as solfège in English, but are spelled with Sharpεn phonemes. We use so instead of the more traditional sol.

- do, re, my, fa, so, la, ty

-

- To these, we add eight, nine, and zero:

- ka, wa, and zy.

- We use Arabic numerals.

- The Sharpεnis words are given below the English in the table headers below. Sharpεn for “solfège” is notɛgh.

- The Sharpεnis word for “number” is solɘr.

-

Notεgh

(Solfège)Solɘr

(Number)Solɘrit

(Ordinal)Solεt

(Planet)Myεth

(Month)Dy

(Day)0 zy zyit Sarzy (Sun) Dyzyit (Sunday) 1 do do doit Doɛt (Mercury) Doɛta (January) Dydoit (Monday) 2 re re reit Reɛt (Venus) Reɛta (February) Dyreit (Tuesday) 3 my my myit Myɛt (Earth) Myɛta (March) Dymyit (Wednesday) 4 fa fa fait Faɛt (Mars) Faɛta (April) Dyfait (Thursday) 5 so so soit Soɛt (Jupiter) Soɛta (May) Dysoit (Friday) 6 la la lait Laɛt (Saturn) Laɛta (June) Dylait (Saturday) 7 ty ty tyit Tyɛt (Uranus) Tyɛta (July) 8 ka kait Kaɛt (Neptune) Kaɛta (August) 9 wa wait Waɛt (Pluto) Waɛta (September) 10 dozy dozyit Dozyɛta (October) 11 doεn doεnit Doεnɛta (November) 12 reεn reεnit Reεnɛta (December) - Sharpεn uses movable do solfège, which distinguishes the names of scale degrees (do, re, my . . .) from the names of the notes. The letters for notes remain the same as in English. The correspondence depends on the key. For the key of F#, the notes are:

-

Scale degree Letter with accidental Note name do F# F-sharp re G# G-sharp my A# A-sharp fa B B so C# C-sharp la D# D-sharp ty E# E-sharp - The Sharpεnis word for “star” is sar; our Sun is the zeroth star: Sarzy.

- Months can be abbreviated with two letters: Do., Re., etc.

- Days of the week can be abbreviated with three letters: Dyz., Dyd., etc.

- Sharpεn forms the ordinals, first, second, and so forth, with the suffix +it:

- doit, reit, myit, fait, soit, lait, tyit, kait, wait

- Sharpεn forms the teens, 11-19, with the suffix +εn:

- doεn, reεn, myεn, faεn, soεn, laεn, tyεn, kaεn, waεn.

- Sharpεn forms the tens, 10, 20, 30, etc., with the suffix +zy:

- dozy, rezy, myzy, fazy, sozy, lazy, tyzy, kazy, wazy.

- Sharpεn forms the powers of ten, 10, 100, 1000, etc., with the root dozy, meaning ten, to which the number of zeros is added:

-

10 ten dozy 100 hundred dozyre 1000 thousand dozymy 10,000 ten-thousand dozyfa 100,000 hundred-thousand dozyso 1,000,000 million dozyla 1,000,000,000 billion (9 zeros) dozywa 1,000,000,000,000 trillion (12 zeros) dozyreεn 1,000,000,000,000,000 quadrillion (15 zeros) dozysoεn 1,000,000,000,000,000,000 quintillion (18 zeros) dozyfaεn - Sharpεn forms the negative powers of ten, 0.1, 0.01, 0.001, etc., with the corresponding ordinal:

-

0.1 tenth dozyit 0.01 hundredth dozyreit 0.001 thousandth dozymyit 0.0001 ten-thousandth dozyfait 0.00001 hundred-thousandth dozysoit 0.000001 million dozylait 0.000000001 billionth dozywait 0.000000000001 trillionth dozyreεnit 0.000000000000001 quadrillionth dozysoεnit 0.000000000000000001 quintillionth dozyfaεnit - Powers of two are similar but the root, re is hyphenated with the power:

- “two squared” is re-re; “two to the minus two” is re-reit

- The verbs don’t have the hyphen but use the verbifying suffix +yn:

- “Double” is rereyn; “half” is rereityn.

- Compound numbers are hyphenated, for example, 21: rezi-do.

- The Sharpεnis word for “dozen” is reεnit. The Sharpεnis word for “pair” or “duo” is reεs (being two) and “dual” is reis.

- As in English, fractions are compounds of the numbers and ordinals:

-

one-half, half do-reit, reit thirds do-myit, re-myit fourths, quarters do-fait, my-fait - Two-quarters is the same as one-half, but you can still say two-quarters: re-fait. The difference between one-quarter and first quarter:

-

one-quarter do-fait first quarter fait doit (literally, the first fourth) second quarter fait reit third quarter fait myit fourth quarter fait fait - Hyphenate the quarters to get the names of the seasons:

-

winter fait-doit spring fait-reit summer fait-myit fall, autumn fait-fait - Dates use the format dd month year or dd/mm/year.

- English: Monday 26 February 2018

- Sharpεn:

- Dydo 26 Reεta 2018

- Dydo rezy-la Reεta re-dozymy-kaen

- Arithmetic operators:

English Sharpεn plus pye minus mye times/multiplied by tue divided by dae squared pre cubed pre-my power of 4, 5, 6, etc. pre-solɘr: pre-fa, pre-so, pre-la . . . square-root dru cubed-root dru-my 4th root, 5th root, etc. dru-solɘr: dru-fa, dru-so,dru-la . . . equals/equal to ku less than yla greater than yga and un (This is the logical operator; the conjuction is e.) or or (This is the logical operator; the conjunction is ro.) exclusive or, xor zor - Example:

- 31 * 3 = 93

- myzy-do tue my ku wazy-my.

Units of measure

- Sharpεn follows the metric system the Gregorian calendar, and the twelve-hour clock for measuring length, mass, ampere, and time, but has its own terms for powers and fractions of the base units.

-

length mytɘr mass gram ampere ampyr time sekond - To these base units, Sharpεn indicates powers of ten, not with prefixes, but by compounding the powers of ten for the larger units and by compounding their ordinals for the increasingly smaller units. For example, “kilogram” is gram-dozyre and “milligram” is gram-dozyreit.

- Here are the metric powers for mytɘr:

-

exameter 1018 mytɘr-dozyfaεn petameter 1015 mytɘr-dozysoεn terameter 1012 mytɘr-dozyreεn gigameter 109 mytɘr-dozywa megameter 106 mytɘr-dozyla kilometer 103 mytɘr-dozymy hectometer 102 mytɘr-dozyre decameter 101 mytɘr-dozy meter 100 mytɘr decimeter 10-1 mytɘr-dozyit centimeter 10-2 mytɘr-dozyreit millimeter 10-3 mytɘr-dozymyit micrometer 10-6 mytɘr-dozylait nanometer 10-9 mytɘr-dozywait picometer 10-12 mytɘr-dozyreεnit femtometer 10-15 mytɘr-dozysoεnit attometer 10-18 mytɘr-dozyfaεnit - In Sharpεn, “time” is tym. Sharpεnis units of time (tym-atoms):

-

instant mom second sekond (Compare the ordinal reit.) minute (60 seconds) minut hour (60 minutes) hora AM, morning dyante noon, midday dymid PM, evening dyaft day (24 hours) dy evening, night nyt week (7 days) dyzty month myεth year an decade anzdozy century anzdozyre timespan span-tym yesterday, today, tomorrow yedy, tody, nedy - Time units that are multiples of a smaller unit, like week and decade, are compounds of the smaller unit and the multiplier number. Week is “days+seven”: dyzty. Compare this to “Saturday,” Dytyit, the “seventh day.”

- Other time-related words:

-

birthday dy-birt annual anis anniversary anisakt

Cardinal directions

-

north nord east yst west wεst south sud - Sharpεn does not follow the practice of subdividing the cardinal directions by alternating between two points, but bases directions on circle of 360 degrees where 0 degrees is north and imagines facing in one of the four cardinal points. Instead of saying “north-east,” a speaker of Sharpεn would say “north right 45” or nord zu fazy-so. Instead of saying “south-south-east,” a speaker of Sharpεn would approximate the point to a degree and say “south left 22” or sud wu rezy-re.

Kinship

- Kinship (kinakt) terms for parents, aunt, and uncle (kin) make gender distinctions; however, children, siblings, neice, and nephew do not:

-

parent bum mother madɘr father fadɘr child, offspring, son, daughter chalɘr sibling, sister, brother zalɘr spouse, husband, wife epɘr aunt tya uncle ɘnk cousin kon niece, nephew nεv - Nevertheless, Sharpεn can identify gender explicitly using adjectives or nouns:

-

adjective female fεm male mεm noun woman humfεm man hummεm

Animals

- Body parts and animals have a special place in the Sharpεnis worldview:

-

arm arm back bak belly bεly blood blɘd body bady breast mun buttock, butt tonεl cheek jya chest chεst chin chin ear yr elbow εlbo eye aku face vigh fat fat finger dita foot fɘt hair her hand man head hεd heart koro heel ary hip hip leg lεg lip lip liver gan knee ghεnu mouth yb neck mog nose nast skin sku stomach stomak thumb ditalan throat gol toe tod tongue lang tooth dεnt - Animals:

-

animal animal bear gom bird tory bull toro cat kat cow moror (like bull/toror) dog dag elephant εlεfant fish fish fox fak frog rana goose gory (like bird/tory) horse uma human hum lion lyon monkey mum (like human/hum) mouse mod rabbit rabit sheep yag tiger tygɘr wolf lob

Colors

- Sharpεn follows the RGB color model by starting with red, blue, and green, and mixing colors from red, blue, and green color names and fragments. This is an additive color model. Plus it adds a few simple names for common mixes, such as gray and brown.

- Color names follow the pattern: consonant-vowel-zh:

-

red ruzh blue bozh green gyzh - Fragments are the initial consonant-vowel pairs: ru, bo, gy.

- Mixes of two colors prefix the fragment of the first to the name of the second:

- Red + blue in the RGB model creates magenta, rubozh.

- Blue + green in the RGB model creates cyan, bogyzh.

- Green + red in the RGB model creates yellow, gyruzh.

- Order is significant. Based on the concept that adjectives follow nouns, the first color is primary and is modified by the second. Rebozh is a bluish red; boruzh is a reddish blue.

- Mixes of three colors follow the same pattern, suffixing two colors to a primary. Red modified by blue modified by green is rubogyzh.

- The absence of color is black, hezh.

- The merging of all colors, red + blue + green creates white, wezh.

- A dark pink is red modified by white: ruwezh; a light pink is white modified by red: weruzh.

- A dark gray is black modified by white, hewezh; a light gray is white modified by black, wehezh.

- A few colors are too common to be represented by mixtures:

- Brown is duzh.

- Purple is puzh.

- The alpha value of a color is its degree of transparency or opacity. In Sharpεn, a kolor has transpor or opakor (nouns) and is transparis or opakaris (adjectives).

- A color may be light or dark. This is the same as having a degree of whiteness or blackness, but different from being in a room that is bright or dark. In Sharpεn, a dark room is a rum dark, and a bright room is a rum bryt.

- François Sudre assigned to the seven phonemes of the Solresol language Isaac Newton’s seven colors of the rainbow, which was clever and easy to remember. Newton’s primary colors were red, yellow, and blue, which combine to produce orange and green, but don’t combine to produce indigo and violet, so they don’t make a good color model.

- In Sharpεn, yndigo is a loan word for the plant, and the color indigo, RGB (75,0,130) is boruhezh (dark redish blue), and violet, RGB(128, 0, 255) is boruwezh (light redish blue).

- These are the names of the colors, that is, nouns. In Sharpεn, to use these as adjectives, add +is. “I played a blue note” is Handεl εsd a not bozhis me.

Grammar

- Words in Sharpεn are not inflected according to tense, case, person, or gender. They are inflected only for showing plurality and possession. There is no distinction between animate and inanimate or between male and female in the pronouns. Verbal tenses are determined by auxiliaries that follow the verbs.

Verbs

- Sharpεn has one irregular verb meaning “to be.” The forms of this verb are used as auxiliaries to express the tenses and modes of regular verbs, except for expressing the present tense, for which a verb retains its basic form without an auxiliary.

- In English, we use modal auxiliaries (will/would, shall/should, can/could, may/might, and must/must) to express various conditionals. In Sharpεn, these conditionals are forms of the verb “to be.”

-

Tense To be Example Meaning Infinitive εsakt

(to be)sab εsakt

(to know)The action is objectified. Present Simple εs

(is, am, are)Sab me.

(I know.)The action is happening. The εs form of the verb “to be” is not used for the simple present of other verbs. Participle εsεnt

(being, existing)Sab εsεnt dinzimεr . . .

(Knowing everything . . .)

a sab-εsεnt luk, a we ɘv sab-εsεnt

(a knowing look, a way of knowing)Represents a present state. Used to introduce an participle phrase (unhyphenated), and as an adjective or noun (hyphenated). Progressive εsεn

(is/am/are being)Sab εsεn me.

(I am knowing.)The action has begun and is continuing. Perfect εsεnεn

(has/have been)Sab εsεnεn me.

(I have known.)The action started in the past and has not finished. Perfect progressive εsεnεnt

(has/have been doing)Sab εsεnεnt me.

(I have been knowing.)The action started in the past and is continuing; the recent activity had a certain duration. Possible εsuk

(can be)Sab εsuk me.

(I can know.)The action is possible; the actor is able. Permissible εsum

(may be)Sab εsum me.

(I may know.)The action is permitted. Conditional εsun

(would be)Sab εsun me.

(I would know.)The action is conditional. Obligatatory εshun

(should be)Sab εshun me.

(I should know.)The action is obligatory, but not happening. Past Simple εsd

(was, were)sab εsd,

(I knew.)The action was completed Participle εsdεnt

(had been)Sab εsdεnt le.

(It had been known.)

a sab-εsdεnt din

(a known thing)The action or state was completed; the past participle can be used to form the passive voice (unhypenated), or to introduce an adjectival phrase (hypenated). Progressive εsdεn

(was being, were being)Sab εsdεn me.

(I was knowing.)The action continues from the present. Perfect (pluperfect) εsεdεn

(had been)Sab εsεdεn me.

(I had known.)The action was unfinished at a certain time in the past; the past action continued for a certain time. Perfect progressive εsεdεnt

(had been doing)Sab εsεdεnt me.

(I had been knowing.)The action started in the past and was continuing. Possible εskud

(could have been)Sab εskud me.

(I could have known.)The action was possible; the actor was able. Conditional εsud

(would have been)Sab εsud me.

(I would have known.)The action was conditional. Obligatatory εshud

(should have been)Sab εshud me.

(I should have known.)The action was obligatory. Future Simple εsεl

(will be, shall be)Sab εsεl.

(I will know.)The action will happen. Progressive εslεn

(will be, shall be doing)Sab εslεn me.

(I will be knowing.)The action will be unfinished at a certain time in the future; the thing will happen without planning or intention. Perfect εsεlεn

(will have been, shall have been)Sab εsεlεn me.

(I will have known.)The action will be completed before a specific future time, but the exact time is unimportant. Perfect progressive εsεlεnt

(will have been doing)Sab εsεlεnt me.

(I will have been knowing.)The future action will be unfinished, but will have reached a certain stage. Possible εskul

(could be)Sab εskul me.

(I could know.)The action will be possible; the actor will be able. Permissible εskum

(might be)Sab εskum me.

(I might know.)The action will be permitted. Obligatory εskut

(must be)Sab εskut me.

(I must know.)The action will be obligatory. - You may use conditional forms of the verb “to be” by themselves (expressing possibility, permission, conditionality, or obligation) to form conditional sentences:

- “Should I?” is ¿Xshun me?

- “Must I?” is ¿Xskut me?

- In English, we use the adverb “not” to negate a verb, clause, or sentence. In Sharpεn, we use the adverb nop or an equivalent negating adverb (“no one” lenop, “nothing” dinop, “nowhere” loknop, “never” tymnop, or “no way” wenop):

- “I do not play the piano” is Handεl nop da pyanan me, or Pyananyn nop me.

- “I never played the piano” is Handεl εsd tymnop da pyanan me, or Pyananyn εsd tymnop me.

- In English, prepositions that follow a verb can significantly modify the meaning of the verb, such as “show up.” In Sharpεn, the verb and preposition would be combined in a single word, shoɘp, although in this case a speaker of Sharpεn would use the word for “arrive,” that is, aryv.

Adjectives

- Sharpεnis adjectives do not have comparative or superlative inflections. Instead, use mor and most. Instead of “pretty, prettier, prettiest,” ase, ase mor, ase most. You can also say “less pretty” ase lεs.

Articles

- The definite and indefinite articles are uninflected.

-

the da a a - These always precede the thing that they are making definite or indefinite.

Plurals

- In Sharpεn, you form the plural

of any noun or pronoun by adding +s or +z, depending on whether it is unvoiced or voiced.

- “One day” is Dy do;

- “Two days” is Dyz re.

- “One month” is Myεth do;

- “Two months” is Myεths re.

- There are no irregular plurals like geese or mice in Sharpεn.

Possessives

- In Sharpεn, you form the possessive by adding +o. This converts a noun or pronoun into an adjective. “One day’s chores” is Korvs dyo da.

- To form the plural possessive, the s or z goes before the o. “Two days’ chores” is Korvs dyso re.

- The plural possessive “women’s” is humfεmso.

Pronouns

- Personal pronouns have singular, plural, and possessive forms.

- Just a reminder about Sharpεn pronunciation. The Sharpεnis first-person singular pronoun me is pronounced like the English “may.” Similarly, de is pronounced like the English “day.”

- In Sharpεn, pronouns have the same form for nominative and oblique cases (as subjects and as objects). Also, the third-person singular does not reflect gender.

-

Pronoun

Sharpεnis (English)Possessive

Sharpεnis (English)First-person singular me (I, me) meo (my, mine) First-person plural mez (we, us) mezo (our, ours) Second-person singular de (you) deo (your, yours) Second-person plural dez (you all) dezo (your, yours) Third-person singular le (one; he, she, it; him, her, it) leo (his, her, hers, its) Third-person plural lez (they, them) lezo (their,theirs) - The reflexive pronoun, regardless of number or person,

is the separate word se, which is not a suffix.

- “I love myself” is Lɘv me se.

- “They love themselves” is Lɘv les se.

Correlatives

- In addition to the personal pronouns, as in English, Sharpεn has correlatives: non-personal pronouns, interrogative pronouns, demonstratives, indefinite pronouns, and quantifiers. As in Esperanto, we put them into a table in categories:

- Query. Interrogative or relative pronouns are used to ask a question or introduce a relative clause. In English, we ask, “Who did it?” and we say “The man who did it is dead.”

- This and that. Demonstrative pronouns represent something near or distant.

- Some. Something indefinite that exists.

- Any. Anything indefinite.

- Another. Another thing.

- No. An indefinite thing that doesn’t exist.

- Each. Each thing.

- Every. Everything.

- All. All things.

- Many. Many things.

- More. More things.

- Most. Most things.

- Other. Other things.

-

Mad

(Adjective)Humo

(Person)Din

(Thing)Loko

(Place)Tym

(Time)We

(Way)Ryson

(Reason)Query wich (which)

huz (whose)hu

(who)wɘt

(what)wer

(where)wεn

(when)hy

(how)wy

(why)This dit, dits

(this, these)dit, dits

(this, these)dit, dits

(this, these)hyk

(here)nogh

(now)so

(thus)ko

(because)That dat, dats

(that, those)dat, dats

(that, those)dat, dats

(that, those)dar

(there)dεn

(then)wedat

(therefore)ko

(because)Some sɘm

(some)lesɘm

(someone)dinsɘm

(something)loksɘm

(somewhere)tymsɘm

(sometime)wesɘm

(someway,

somehow)Any εny

(any)leεny

(anyone)dinεny

(anything)lokεny

(anywhere)tymεny

(anytime)weεny

(anyway,

anyhow)Another mordo

(another)lemordo

(another

one)dinmordo

(another

thing)lokmordo

(another

place)tymordo

(another

time)wemordo

(another

way)No nop

(no)lenop

(no one)dinop

(nothing)loknop

(nowhere)tymnop

(never)wenop

(no way,

no how)Each gε

(each)legε

(each one)dingε

(each

thing)lokgε

(each

place)tymgε

(each

time)wegε

(each

way)Every imεr

(every)lezimεr

(everyone)dinzimεr

(everything)lokzimεr

(everywhere)tymzimεr

(everytime)wezimεr

(everyway)All al

(all)lezal

(all of them)dinzal

(all things)lokzal

(all places, universe)tymzal

(all times, always, forever)wayzal

(all ways)Many hyju

(many)lezhyju

(many

of them)dinzhyju

(many

things)lokzhyju

(many

places)tymzhyju

(many times)wezhyju

(many ways)More mor

(more)lezmor

(more

of them)dinzmor

(more

things)lokzmor

(more

places)tymzmor

(more times)wezmor

(more ways)Most most

(most)lezmost

(most of them)dinzmost

(most

things)lokzmost

(most

places)tymzmost

(most times)wezmost

(most ways)Other odro

(other)lezodro

(others,

other ones)dinzodro

(others,

other things)lokzodro

(other

places)tymzodro

(other

times)wezodro

(other

ways)ko-odro

(otherwise)

Prepositions

-

about abut above sɘp across trans after aft against alan along y amid amid among, between intɘr around ɘm at agin before ante behind dera below, beneath, under, underneath sɘb beside bysid beyond tran by (close to) ba considering konsidɘr during dɘrεn except εksεpt for for from frɘm in in into intu like sav of ɘv off fɘ on ɘn onto ɘntu out at over ovɘr per pɘr plus plɘ through thru throughout thruat till, until til to, toward tu up ɘp upon ɘpan versus vεrsɘs via vya with wid within widin without widat

Conjunctions

- Sharpεnis conjunctions are similar to the Unish words:

-

also also although do and e as zo because ko but bu if if or ro since sint so so while wyl yet yεt (can also be an adverb)

Word-order

- Word-order of sentences in Sharpεn is verb - object - subject.

- Sharpεn forms a present participle of any verb

by following it with the present participle of “to be”:

- “I am playing the piano.” Handεl εsεnt da pyanan me.

- When the verb is intransitive, then you get verb - subject:

- “I am swiming.” Swim εsεnt me.

- An article (a, the) precedes the noun it identifies.

- An adjective follows the noun it modifies;

an adverb follows the verb it modifies:

- “I am playing the black piano,” Handεl εsεnt da pyanan hei me.

- “I am swimming slowly.” Swim εsεnt sloky me.

- The general rule that modifiers follow the modified affects compounds. The main idea comes first. For example, “word order” is ord-mot.

- Also, Sharpεn favors suffixes rather than prefixes. For example, “irregular” is regulisnop (literally “regulate +ness +not”).

- Subordinate clauses follow the main clauses:

- “Am writing the poem interesting I, when am inspired I.”

- Omit the subject to make an imperative sentence: verb - object. “Love yourself” is Lɘv se.

- Like English, passive declarations leave out the subject and convert

the verb into a past participle:

- “You are loved.” Lɘv εsdεnt de.

- Begin with an inverted question mark to make a question. Keep

the same word-order. An interrogative pronoun follows the opening punctuation.

- “Do you play the piano?” ¿Handεl da pyanan de?

- “How do you play the piano?” ¿Hy handεl da pyanan de?

- “Why do you play the piano?” ¿Wy handεl da pyanan de?

- “When will you play the piano?” ¿Wεn handεl εsεl da pyanan de?

Translation

- A speaker of English like me is interested in translating English to Sharpεn, and Sharpεn to English. Sharpεn is not a cipher of English, so the first part of the translation process is mapping the grammar of the source language:

- Use punctuation to break it up in to sentences.

- For each sentence, look up each word

to determine its part of speech: noun, verb, adjective, adverb, article,

conjunction, and so forth.

- This determination must group verbal particles and auxiliaries. For example, in English “has been playing,” (present perfect tense) must be kept together, and in Sharpεn handεl εsdεnt must be kept together. These verbal phrases must be treated as one part of speech without losing information about their tenses.

- When translating from English, this determination must identify the roots of irregular words in English (“went” is past tense of “to go,” “geese” is plural of “goose,” and so forth).

- When translating from Sharpεn, this determination must identify any auxiliary that determines the tense of the verb.

- It is helpful to think of the third-person singular in English as the pronoun “one” before translating from English to Sharpεn. For translating from Sharpεn to English, the gender of the pronoun is not known, so le would always be translated into “one.”

- Identify relative, dependent, subordinate clauses.

- For each clause and the main part of the sentence, match the pattern of parts of speech to a known pattern for the language to determine the subject, verb, object, and modifiers (words and clauses).

- Determine the proper order of parts for the target language.

- In order, plug in the translation for each word.

- The gender of third-person singular pronouns in English is lost when translating into Sharpεn, and when translating from Sharpεn into English, we use the English pronoun “one.”

Translating verbs

- In English, an irregular verb typically has one of only a few forms, and the rest of the tenses and modes are formed with auxiliaries. After we identify the auxiliaries and the form of the main verb, the Sharpεnis translation is unambiguous.

- This is illustrated with the verb “to know”:

-

- Simple present: “know.” The simple present is a base that forms other present and future tenses with auxiliaries:

- Infinitive: to + simple present: “to know.”

- Present possible: can + simple present: “can know.”

- Present permissible: may + simple present: “may know.”

- Present conditional: would + simple present: “would know.”

- Present obligatory: should + simple present: “should know.”

- Simple future: will + simple present: “will know.”

- Future possible: could + simple present: “could know.”

- Future permissible: might + simple present: “might know.”

- Future obligatory: must + simple present: “must know.”

- Present participle: “knowing.” This forms other tenses with auxiliaries:

- Past progressive: was/were + present participle: “was knowing.”

- Past perfect progressive: had + been + present participle: “had been knowing.”

- Future progressive: will + be + present participle: “will be knowing.”

- Future perfect progressive: will + have + been + present participle: “will have been knowing.”

- Present third-person singular (inanimate): “knows.” These translate into the simple present form in Sharpεn. The verb “be” also distinguishes:

- Present first-person singular (animate): “am.”

- Present third-person plural: “are.”

- Simple past: “knew.”

- Past participle: “known.” This forms other tenses with auxiliaries:

- Past perfect: had + past participle: “had known.”

- Past possible: could + have + simple past “could have known.”

- Past conditional: would + have + simple past “would have known.”

- Past obligatory: should + have + simple past “should have known.”

- Future perfect: will + have + past participle: “will have known.”

- In the English-Sharpεn lexicon, the verb “know” is represented with tags that identify the verb tense:

know=ns/knew=ps/known=pp/knows=n3/knowing=np:sab:v-

=i infinitive (used only for Sharpεn) =ns present simple -- “n” symbolizes the present, as in “now” =n3 present 3rd-person singluar =np present participle =ng present progressive =nf present perfect =nv present perfect progressive =na present possible =nm present permissible =nc present conditional =no present obligatory =ps past simple =pp past participle =pg past progressive =pf past perfect =pv past perfect progressive =pa past possible =pc past conditional =po past obligatory =fs future simple =fg future progressive =ff future perfect =fv future perfect progressive =fa future possible =fc future permissible =fo future obligatory - If tenses are not tagged in the lexicon, a verb is assumed to be regular; that is:

- +s to form the present third-person singular.

- +ing to form the present participle.

- Simple past and past participle:

- Double the final consonant and add +ed if there is a single stressed vowel before the final consonant.

- +d if the simple present ends in E.

- Drop the Y and +ied if the simple present ends in Y.

- Otherwise, +ed (or, if the simple present ends in D, add +d)

The Sharpεnis language is not a milestone in the history of science, but like most the poems in The book of science, it has been inspired by milestones in the history of science. Constructing a language is similar in many respects to making a painting or writing a poem.

Mark Rosenfelder describes over three hundred constructed languages; Glottolog classifies 7,695 natural and constructed languages. Clearly, this is a crowded field, and I do not expect Sharpεn to stand out. There are many far more clever and more useful conlangs to study.

As an English-speaker, constructing a language is one way to increase one’s appreciation for the complexity and expressiveness of English. Just think, for example, how many ways you can say “yes” in English:

The Sharpεnis lexicon is much more limited.

Like all of my works that are online, I revise and update this language without notice. Issues that I intend to resolve by analysis and translation include:

See also in The book of science:

Readings in wikipedia:

Other resources: