James Ferguson

thermometry

|

Pyrometer

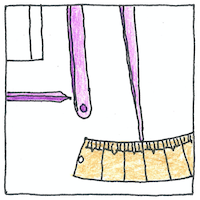

James Ferguson, in 1759, made “bars of different metals, as silver, brass, and iron; all of the same length,” and placed the flame of a spirit lamp under each for the same number of seconds to find “the relative expansion of different metals” by mounting two levers on a mahogany board, adjusted by hand to press against the end of the heated bar and point to a scale marking an expansion accurate to the four-thousandth part of an inch, but found this first attempt “defective both in principle and in execution” so made, in 1764, his “new pyrometer” a finer instrument for the same purpose, showing an expansion accurate “to the five-and-forty-thousandth part of an inch.”

Relative expansion

Ferguson’s new pyrometer could show only relative thermal expansion. It was not designed nor could it be callibrated to determine temperatures, as attempted later by Guyton and Daniell.

A metal

conducts heat and electricity and expands when heated expands softens fuses melts ferromagnetic paramagnetic malleable or brittle base or precious. It makes a pretty penny, a bauble for a beauty, a plate of pewter, a can of corn, a tower of steel, a cable that suspends a bridge, a wire that connects the world, a ring that symbolizes oneness.

That some elements as common and seemingly non-metallic in compounds such as table salt are metals has always seemed a mystery to me. That some metals, such as cobalt, are both toxic and essential to life seems even more mysterious.

See also in The book of science:

Readings in wikipedia: