Pierre de Fermat

optics

|

Fermat’s principle

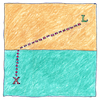

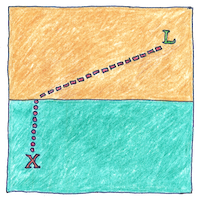

An old question in optics is why, if light radiates in all directions, why does it seem as though light travels in a single line from an object to the eyes? Alhazen thought it must be that we see only the rays that hit the eyes perpendicularly. Fermat said, simply, a ray of light always takes the fastest available path, not necessarily the shortest path, as a lifeguard who rescues a swimmer at a beach runs along the shore to a closer point before diving into the waves where he moves more slowly. Or if two rays of light diverge from a distant object and a lens focuses them both at the same point, then the outer ray must have a shorter path in the lens so that the two rays arrive at the same time.

A modern explanation

Light on nearby paths reinforce . . . while other paths interfere . . . so as to disappear.

Assumptions

Descartes assumed that light was instantaneous; Fermat assumed that its speed was finite. Descartes assumed that light travels faster in denser materials; Fermat assumed that light travels slower in denser materials. At the time, the speed of light was difficult to measure. Too often it appears that reality conforms to our expectations. If it doesn’t make sense, it’s not necessarily because it’s wrong.

Light has a constant speed, c, only in a vacuum. In other transparent materials, light travels more slowly. The ratio of the speed of light in a vacuum to the speed of light in a material is called the refractive index. For example, in glass light travels about two-thirds of c, so its refractive index is about 1.5.

See also in The book of science:

Readings in wikipedia: